what the goo goo dolls (and buffalo) taught me about being an underdog

In a way, the worst thing an underdog could do is win. There’s a reason why sports movies about underdogs end after the winning goal–because what comes next will not be inspirational or romanticizable. The victorious underdog immediately surrenders the very reason why everyone was rooting for them. Like winsome child actors who grow up into painfully ordinary-looking adults, they graduate out of the public’s sympathies. Now what? Keep winning? Good luck, kid. We were only rooting for you because we never thought you’d win in the first place.

On the back cover of their 1987 debut album, we see three photos of the Goo Goo Dolls in a bar. Not performing music in a bar, just … in a bar. In one shot, they pose with an elderly man who looks like a live-action Andy Capp. In another, they ham it up behind twenty or so empty beer bottles. Taken with a harsh flash in a dark room, they’re photos you might pass around for laughs–not publish to professionally represent you. But fair enough, the photos do, in some sense, represent the contents of the album: thirty-four merciless minutes of jackrabbit thrash-punk. It’s beautiful in the same way that fire can be beautiful, even if it has engulfed your car, now overturned in a ditch.

photos by mark dellas

It’s not completely accurate to call the Goo Goo Dolls underdogs in 1987–not because no one expected them to win, but because I don’t think they were even trying to win, at least not in the traditional sense. Punk offers a third path in the win/lose binary; if you actively reject mainstream success, you preempt being a loser. And if there is a lyrical theme to that first album, it’s that we are sometimes participants in our own destruction, a familiar theme of the genre. Song titles alone illustrate this point: “Torn Apart,” “Messed Up,” “Beat Me.” But even in those early days, the Dolls hinted at a restless longing. “Hard Sores” expresses contempt for a reckless punk. “Different Light” depicts a speaker who yearns to be understood beyond the present context, and, despite its disagreeable title, “Slaughterhouse” is a lonely ode that mentions flowers, trees, and children’s tears. But the song that best represents this larval phase of their development is “I’m Addicted.” Robby sings: “Look around this dirty town / Drink it up till we fall down / Don’t want to forever live this way / But it’s gonna have to do for today.” Then the chorus that, with its ascending melody, almost sounds hopeful: “I’m addicted … as I want to be.” Those are the lyrics I hear when I see their young, wasted faces on the back of that album jacket.

I think the Goo Goo Dolls made a move from unruly punks to budding underdogs with the release of 1989’s Jed. The playing was tighter and, in contrast to the brooding sound of their debut, the music feels more like a shambolic celebration of life–life in the gutter, but life nonetheless. The lyrics more clearly indicate a growing impatience for something more. The opening track, “Out of Sight,” shrugs off the aging popular kids and their conventional life paths–manufacturing jobs and marriage–while the propulsive “Road to Salinas” surrenders to a melancholic awareness that home is a hard place to leave. “Had Enough,” a song I would consider putting on my list of all-time favorite songs, heartbreakingly admits: “I know what I need, but I won’t follow [and] I can’t lead.” There’s only one photograph on the album jacket of Jed. They’re still in a bar–the now-defunct and oft-grieved Continental–but this time they’re at least kicking ass on a stage.

Buffalo has long been an underdog town. During the Blizzard of ’77, Johnny Carson joked, “We could have told you Buffalo was a disaster area before President Carter’s declaration.” When six men in Lackawanna were arrested in 2002 for ties to Al-Qaeda, the next Tonight Show host, Jay Leno, said, “[P]rison is too good for these people. Let’s leave them in Buffalo, let them die of boredom.” Then there’s the time that CNN’s Anderson Cooper descended into a fit of uncontrollable laughter on air, calling Buffalo’s Dyngus Day festivities “stupid [...] really so stupid.” The years of national slights are not entirely without cause: bad weather, declining population, rising poverty, crumbling infrastructure, and, yeah, sorry, losing sports teams. More on that later.

I grew up in the East Lovejoy neighborhood of Buffalo, nicknamed “Iron Island” for the train tracks that surround it. As a kid, my imagination was taken by the many empty storefronts and faded signs that advertised products and places that no longer existed. It was hard for my young mind not to perpetually wander backward, since, in the early ’80s, Lovejoy Street–the central street that once hosted about ten blocks of stores and businesses–save for a bar, a pizzeria, and a couple shops, felt more like an abandoned theater set than a functioning main street. This ghost town feeling was only exacerbated by the mournful sound of train brakes. I remember lying in bed on humid summer nights, falling asleep to their haunted howling. Before the Buffalo Central Terminal was built, Lovejoy Street was about three times longer, ending short of Jefferson Avenue. The story of Buffalo’s Central Terminal parallels the fate of the city itself. Built two-and-a-half miles away from downtown, anticipating a downtown that would expand to meet it, the majestic Art Deco edifice opened in the summer of 1929–just four months before the Wall Street crash would essentially put an end to recreational travel. The station fell into a state of permanent decline after World War II until it finally closed in 1979. It stood abandoned for years, a symbol of Buffalo’s lost potential. As a kid, I could see the clock tower from our second-floor apartment window. Lovejoy Street on the Western side of the train tracks was renamed Paderewski Drive, fanning out from a traffic circle in front of the Terminal. The other major street on that circle is Memorial Drive, which ends about five blocks east at Broadway. Yes, that Broadway. The one that appears in the Top 40 Goo Goo Dolls song.

In the summer of 1989, when I was thirteen years old, a friend of a friend introduced me to punk music: the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, and this band that’s actually from Buffalo–the Goo Goo Dolls. I bought a cassette copy of Jed from the now-defunct Cavages at the now-defunct Thruway Mall, and it quickly became my favorite album. It offered all the angst of the rock and metal music I previously enjoyed without the overt sexism and tasteless machismo. I guess most of the music I discovered that summer did that, but the Goo Goo Dolls felt extra special because they were from my city. Little did I know then, but guitarist/singer John Rzeznik grew up on Clark Street, a two-mile walk from where I lived, and only one block away from the street I lived when I was a baby. We both saw that clock tower from our childhood homes.

What punk taught me is that identifying as an underdog can be empowering. Sure, as a white boy in a racist, patriarchal society, I benefited from privileges, but I was an awkward, skinny, sensitive, somewhat effeminate white boy who hated sports. I was attracted to girls, but not exclusively. The other boys let me know, in so many ways, that I was different. I would learn to adapt to the unwritten laws of masculinity, but not without my share of internalized shame. To make things harder, I was the product of a marriage ended by domestic abuse and alcoholism, growing up working poor in a single-parent household. But punk! Punk gave me an outlet to express my pain and the permission to be different. Punk offered hope to those who felt alienated by mainstream values (both musical and social) by eschewing them altogether. Winning is for losers, it seemed to suggest. Try this alternative path.

I have little doubt that punk made a similar proposal to the young Goo Goo Dolls. The blueprint for fall-down-drunk punks with a poet’s touch is The Replacements, a band the Dolls have openly admired. Primary songwriter Paul Westerberg gave them the lyrics for their 1993 song “We Are the Normal” and both Robby and John appear in the 2011 fan-centric Replacements documentary Color Me Obsessed. The Dolls’ 1990 album Hold Me Up, in which they become full-fledged underdogs by scoring a video on MTV, often upscales the more romantic moments of The Replacements’ 1987 Pleased to Meet Me, taking the bittersweet songcraft of “Valentine” and turning it into pure power pop gems like “There You Are” and “Just the Way You Are.” But The Replacements found themselves prisoners of their underdog status, famously shooting themselves in the foot whenever success came too close. They’d intentionally bomb high-stakes shows, letting them dissolve into nights of sloppy-drunk cover songs. They once stole what they believed were their master tapes and rolled the reels into the Mississippi river. Their big break on SNL was so unruly and chaotic that it ended in their being banned for life. And this is a band that wanted to hit it big, as big as their friends R.E.M.

What punk also taught me is that identifying as an underdog can be damaging.

I may be one of the few people in Buffalo to have never watched a full sporting event, let alone a Bills game, but even I felt the anguish of losing the 1991 Superbowl to a single wide-right field goal. And then to lose the next Superbowl? And the next? And the next? Losing four Superbowls in a row is a really peculiar thing. It’s hard to call us underdogs if we were able to repeatedly prove ourselves one of the two best teams in the NFL. But to lose that final game four times in a row? Maybe that’s why Baltimore sports radio host Jerry Coleman called us a “city of losers.” Hey, I don’t agree with him, but what are we then? Almost winners? Professional losers?

I’ve been hearing about an impending Buffalo renaissance my entire life. And while it seems we’ve made some progress since our rust belt days of the ’70s, try telling that to the forty percent of our kids who live in poverty, drink lead-poisoned water, and attend failing public schools. If I meet promises of progress (often in the form of private development) with cynicism, it might be because I’ve seen enough of these promises fall short, but it might also be the residual effects of growing up in an underdog town. At some point, I started to identify with decay and abandonment. Every barely legible, hand-painted sign said, this is what I could have been. And maybe that’s how I started to think about myself, someone who could have been something, had I been born in another era. Or another city. Another family. As a young adult, I felt like the abandoned clock tower of the Central Terminal: useless, needing to be saved, a symbol for wasted potential.

The yellow bus I took to school every day in the early ’90s went down Broadway, making its way to William Street and finally Clinton, where I disembarked near enough to downtown to get that fresh Cheerios smell from the General Mills plant. That daily drive was a tour of a city that essentially no longer existed–deteriorating husks of department stores, dry cleaners, theaters, and churches. I saw the immediate sadness of spaces that no longer had anything to offer a community, and the idealist in me ached at the sickening wastefulness of it all. But, like the emptiness of my own neighborhood, the romantic in me appreciated the cruel beauty, the peeling paint, the cracked windows, the broken loneliness. Home sweet home.

To my surprise, some of these buildings appeared in the inner booklet of the Goo Goo Dolls’ 1993 album Superstar Car Wash, including the car wash itself. Even before the album’s release, I loved that building for its charming audacity. We all knew there’d be no superstars getting their cars washed in that modest cinderblock garage on William Street, but that didn’t stop the owners from assembling the mirrored letters that reminded us that it’s always possible to feel like a superstar. That album is a turning point for the band. It’s on a major label. It’s less punk. It was more likely to be heard right of the dial. I understand and accept these changes now, but when it was happening, like many of their early fans, I will admit that I felt a little left behind. And when their next album–1995’s A Boy Named Goo–went double platinum and “Name” was all over the radio, I was happy for them, but things were different. They were no longer underdogs. They were winners–actual superstars.

The first time I saw the phrase “Keep Buffalo a Secret,” it immediately resonated with me, and when I learned that someone was brazen enough to paint it on the side of a three-story building downtown, all-caps blue on white, I was over the moon. It’s practically conceptual art. I loved the contradictory nature of the message. Slogans are supposed to promote, but this one asked us not to. And how can anything be a secret when it’s announced on a forty-foot wall? In a recent video call with Brett Mikoll, the co-founder of Oxford Pennant who came up with the tongue-in-cheek phrase, I wondered aloud if, secretly, Buffalonians didn’t exactly want a renaissance. “We are starved for validation, always,” he said. “We want to be seen, but we don’t want to be loved that much. We want just enough [love] that we’re on everybody’s radar, but then still to be everybody’s underdog and still be underappreciated.” Mikoll’s a Buffalo native and successful business owner, so I asked him about the cumulative effects of being an underdog. His answer surprised me, shifting my thinking on the subject. He sees Buffalo’s underdog reputation as an asset: “I think it’s freeing. I think that because the expectations are very low, or don’t exist at all, the place is, a lot of times, an afterthought, and that it gives you the freedom to, I mean, take your pick–get weird with stuff, try things out, and if they don’t succeed or don’t meet whatever expectations you have in your mind, it’s, like, no harm, no foul. No one was expecting anything anyway.” Indeed, there is freedom in a lack of success, and art, in particular, thrives on freedom. The Goo Goo Dolls’ first three albums have their share of experimentation, from the incoherent muttering that opens their debut, to the wonderfully weird choice to have lounge singer Lance Diamond sing a few songs, to the decision to record the single-worthy “Two Days in February” on a street corner. But as Kris Kristofferson wrote, “Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.” Getting signed to a major label involves a large financial investment. Suddenly, a lot of people have a lot to lose.

Here, I thought I would have to concede that, when it comes to being an underdog, there’s a difference between sports teams, bands, businesses, and cities. Isn’t the concept of winning too simplistic for anything outside of sports? Doesn’t art demand something more nuanced than the win/lose binary? But the more I thought about my conversation with Brett Mikoll, the more I realized that success itself is a slippery concept, too subject to interpretation. I mean, it’s true that the Bills never won the Superbowl, but in so many other ways, they have proven themselves a successful team. Mikoll said that the key to being an underdog is truly believing that you deserve better. Doing so “puts a lot of gas in your tank to accomplish things or to have a voice, or have ambition.” And for him, particularly as a business owner, freedom and control are integral to success. “Owe no one,” he says. “If you owe no one, you are fully in control of the successes and mistakes. [...] If you start out as an underdog and you keep as much control as you can, you get to have all the glory, or learn the hard lessons. Either way, it’s still a great feeling versus it being done for you.” I think Mikoll’s optimism is aligned with the language of the pennants and banners he creates and sells. The medium calls for an us-against-the-world mentality. It’s the voice of teams and summer camps, communities bound by a desire to survive, and this thought makes me love the idea of Oxford Pennant even more. It’s currently one of Buffalo’s most successful independent businesses, striking partnerships with Wilco, Weezer, Joni Mitchell, and the estate of John Prine–artists who’ve exercised their creative freedom even when it didn’t always translate to an increase in sales. And their most notorious slogan–Keep Buffalo a Secret–while maybe a little disagreeable on the surface, is born out of a desire to protect the city it loves. It aims to preserve what makes Buffalo special in the first place. “Buffalo is a city with so much opportunity,” Mikoll told me, “where we don’t have to play by the rules of other cities.” This is where I wonder if Keep Buffalo a Secret is actually entertaining a fantasy–maybe we can stay underdogs forever.

Go, team, go… but not too far.

Having listened to their full discography, and having grown up in the same parts of town as Rzeznik, I am struck by the thematic shift in the Goo Goo Dolls’ lyrics as they settle further into fame. Long gone are the days of romanticized destruction. The post-underdog Goo Goo Dolls sing about preservation. We see early glimpses of this on 1998’s “Broadway,” a song I always felt was a sober take on Westerberg’s “Here Comes a Regular.” More recent material is forthright in its sincerity, in its mission to inspire and possibly save. “Souls in the Machine” (2016), at the nadir of its anthemic chorus, offers the hopeful line: “Every breath’s a moment / Every moment is a chance to live again.” “You Are the Answer” (2022) tells listeners, “Your only crime is being alive / You know you’re not alone / You are the answer you’ve been looking for.” “Run All Night” (2025), like a supportive friend, offers the following imperatives: “Don’t let your dreams die young / Don’t let your heart go numb / ’Cause all we got is just one life / You better run all night.” I attribute this thematic shift to the band’s Buffalo roots, to growing up in a town that no one expected anything from, to associating home with decay and abandonment. I say this because I, too, changed my course, abandoning a punk distrust of authority to become an earnest high school English teacher. It seemed like one of the few jobs where you could really make a positive difference in the lives of other people. For some recovering underdogs, this is part of the process of overcoming its psychological toll–if you can save yourself, you can save others, too.

However, I’m willing to bet, and I say this based on my own experience, that, with every inspirational lyric and positive affirmation, Rzeznik is also still trying to save himself. Those with the most doubt are also often the strongest proselytizers, a notion suggested by social psychologist Leon Festinger (the originator of the theory of cognitive dissonance). In 2010, David Gal and Derek Rucker held this idea up to experimental scrutiny and published their results in Psychological Science. They found that “people whose confidence in closely held beliefs was undermined engaged in more advocacy of their beliefs.” I feel the sting of that truth every time I find myself trying to convince a room full of teenagers that art matters, that reading literature makes you a better person. (It does, doesn’t it?) Nonetheless, winning won’t heal the scars of being raised an underdog. In fact, anyone who has transcended their socioeconomic class will tell you that it often leaves you straddling two worlds, at home in neither, left to navigate two distinct sets of values on your own. It’s actually a hard sell, winning. It can be traumatic, and being saved from any kind of trauma is like learning to swim just before you’re swept over a waterfall. You’re only safe for as long as you are able to keep swimming against the current.

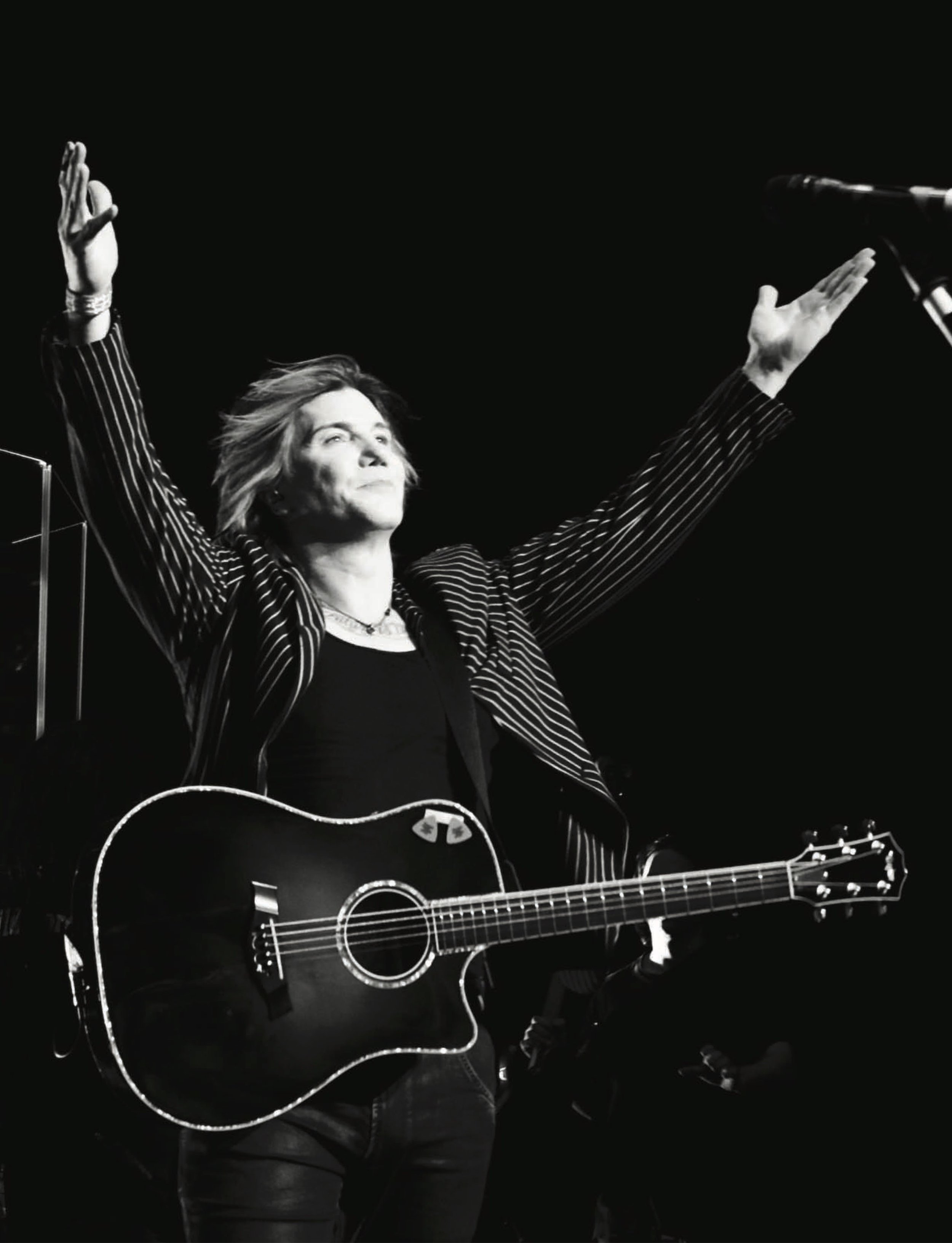

When the Goo Goo Dolls recently played their sold-out show at Buffalo’s fourteen thousand-capacity Key Bank Center, I often looked out at the audience. They’d have to play 106 sold-out shows at The Continental to entertain that many people. The Continental was a club for underdogs, a place where people grumbled about bands selling out. The arena, on the other hand, was filled with people of all ages and all walks of life, coming together to celebrate the music of a band that, for well over thirty years, has delivered messages of strength and honesty and hope. It was joyous. No doubt the Goo Goo Dolls sacrificed freedom and control when they set their sights on mainstream success, but, in a move that I’ll always admire, they exchanged that loss for the power to inspire en masse, summer anthem after summer anthem. It is one of the most noble ways to graduate out of underdog status.

There’s one more little detail about the back cover of the Goo Goo Dolls’ 1987 debut that I want to address. It’s the phrase “I beg your pardon, but I never promised you a rose garden,” which is printed twice in a row. It comes from the 1967 Joe South song “Rose Garden” and supports the pragmatic understanding that “there’s gotta be a little rain sometime.” It also speaks to the notion that all parties enter a relationship with expectations. I like the punk rock attitude of Oxford Pennant’s “owe no one” way of operating, but the truth is that–whether you’re talking about a romance or a band or a business or a city–someone is always expecting something.

There are many variables when we try to define success, but in every discipline, we begin by owing something to ourselves. That’s where integrity is born. It is perhaps too easy for the underdog, free of expectations and obligations, to remain pure and true. However, once we draw others in–whether they are fans or customers or citizens–our debt grows. Maybe the key to maintaining integrity is to ask regularly: what do we owe … and to whom? Even rose gardens expect the promise of rain.

in print