ani

The sky is blue gray over Ohio and ripe peach over Fort Erie and in between a half moon shines brighter than any of the stage lights. Sitting, standing, lounging, and strolling the grounds of the new-ish Terminal B venue on the Outer Harbor, Buffalo has turned out strong for one of its own–Ani DiFranco, back for her first hometown show in almost a decade.

It’s August 31, 2025, and the temperature is about to drop below seventy for what feels like the first time this summer. Six thousand fans fill the former shipping terminal and listen to the opener, Alynda Segarra’s Hurray for the Riff Raff. Local fans haven’t had a chance to see DiFranco here since August 26, 2016, when she appeared at Asbury Hall, the former Methodist church-turned cultural crossroads that DiFranco and Scot Fisher saved from demolition in the late 90s. The occasion was the rebirth of “Babefest,” a politically engaged celebration DiFranco had first launched in New York City in 2000. The nine years after Babefest have been full of unprecedenteds, for DiFranco as for all of us–and now she’s back to sing about it.

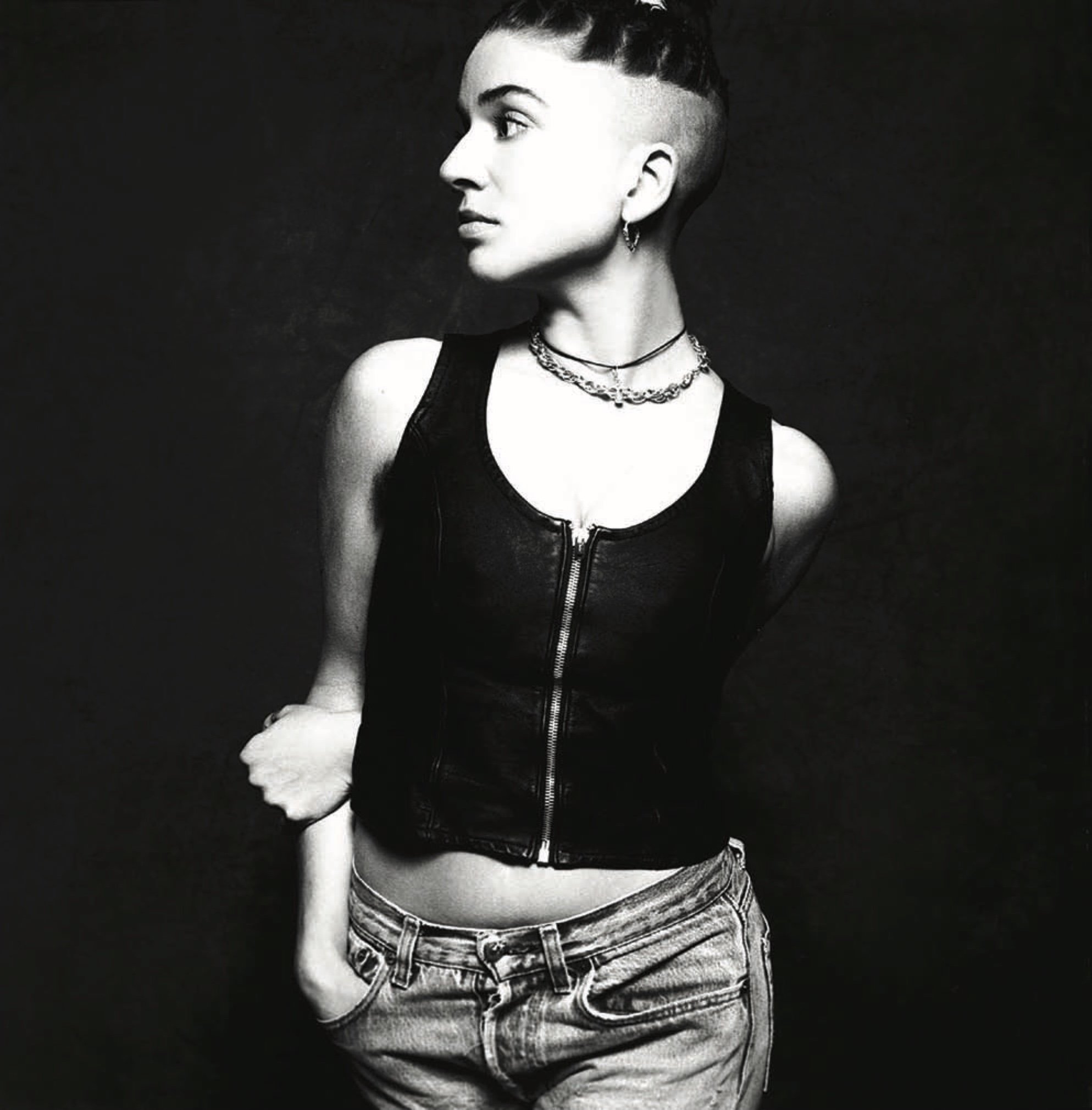

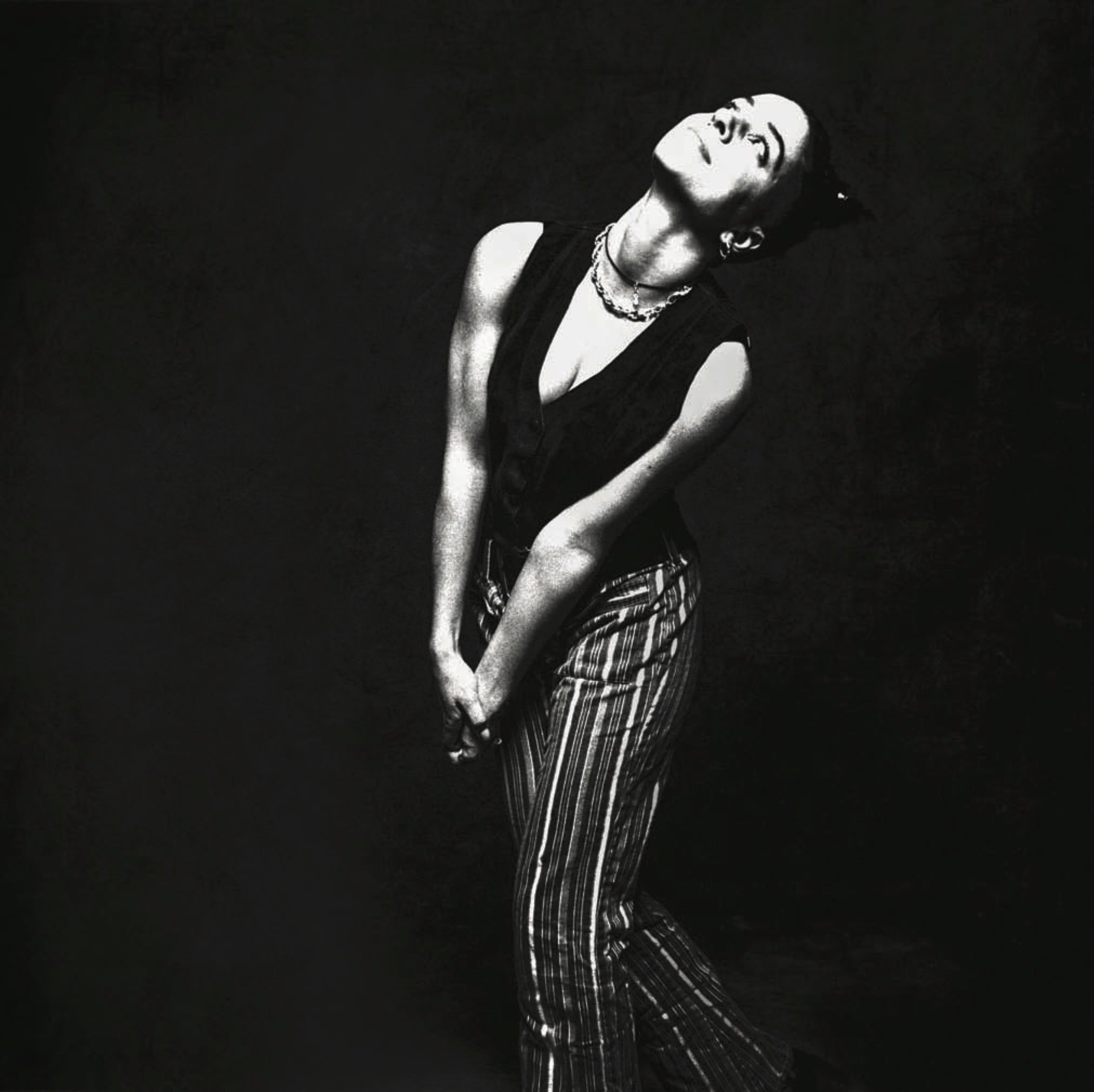

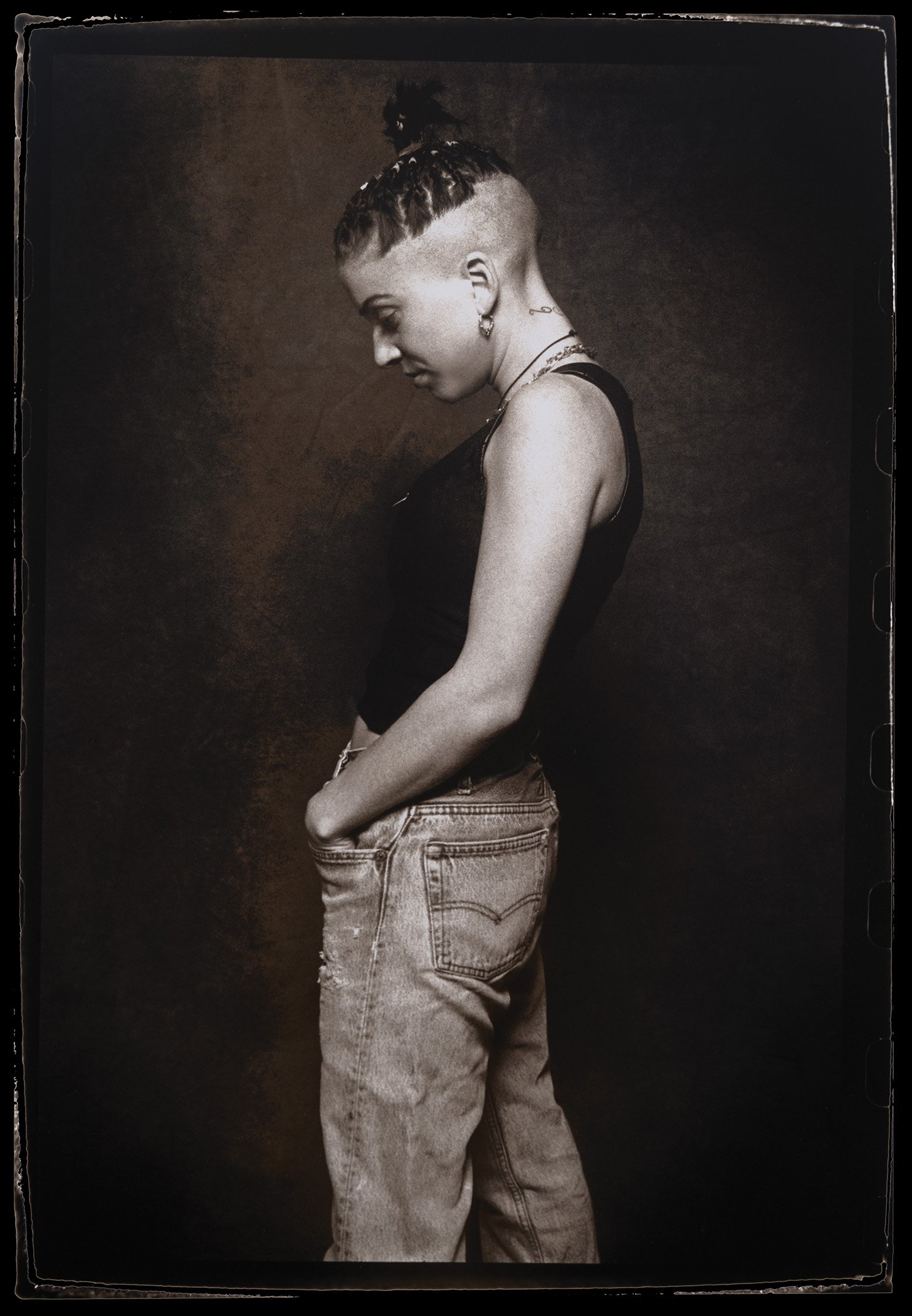

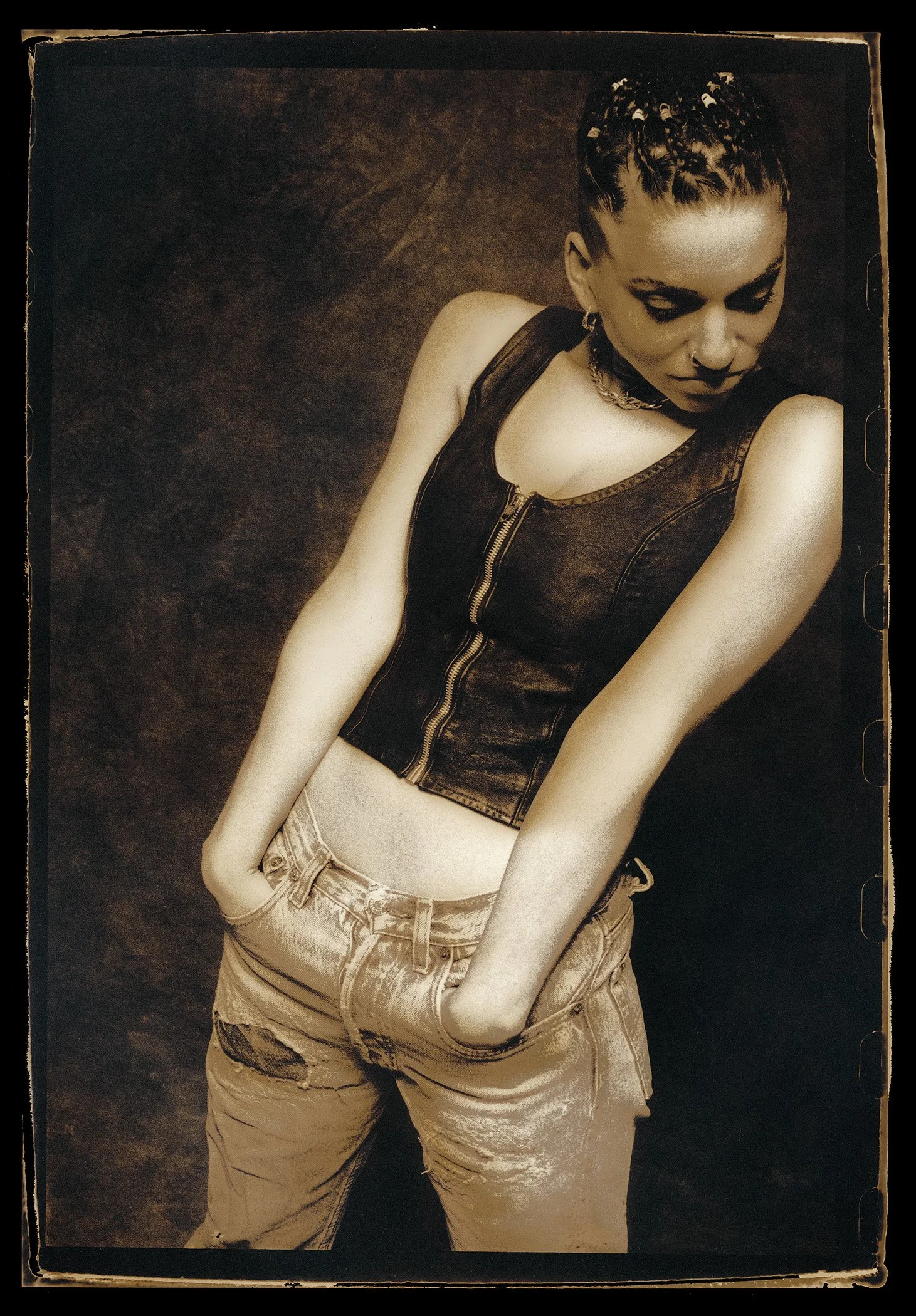

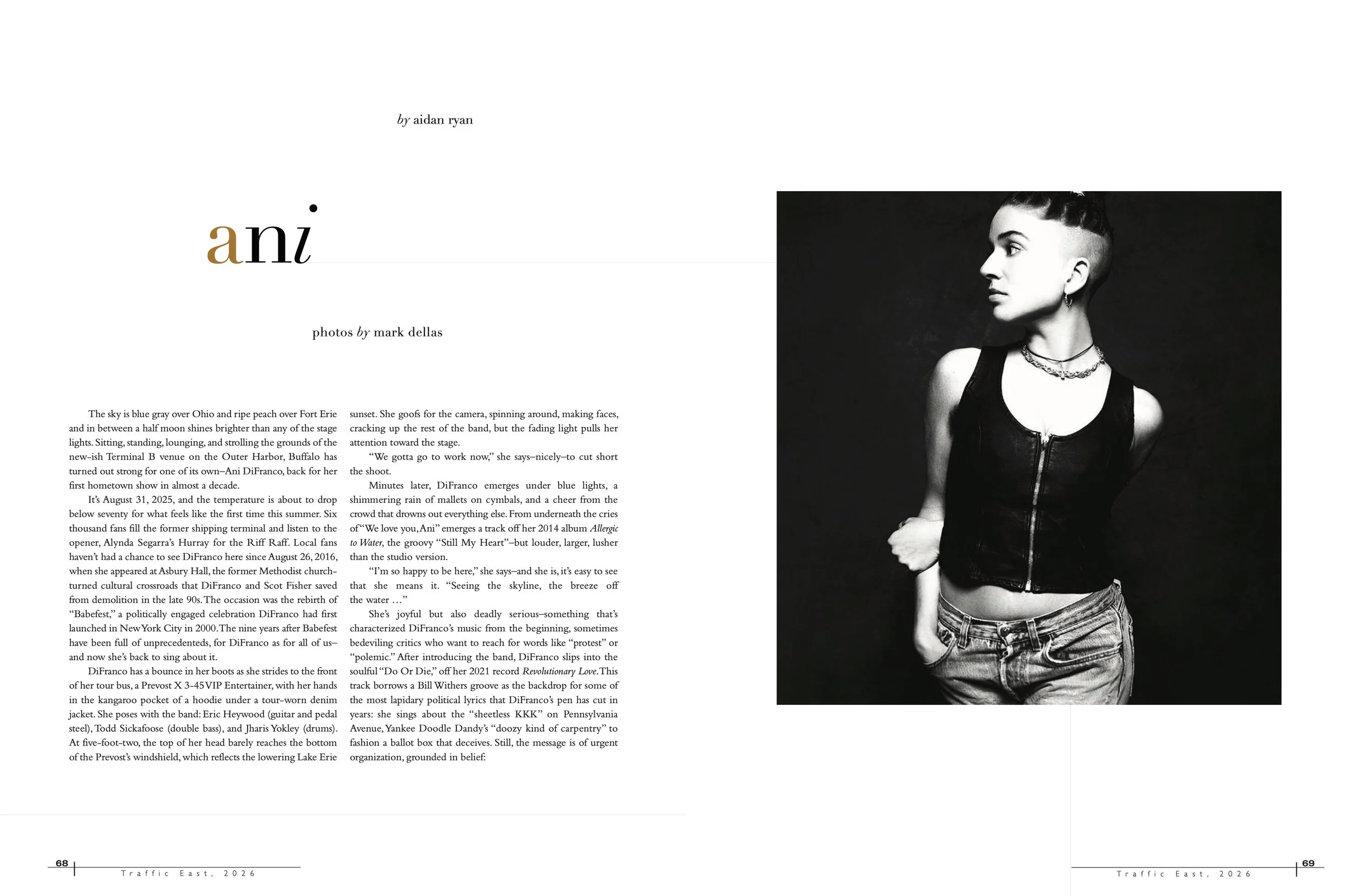

photos by mark dellas

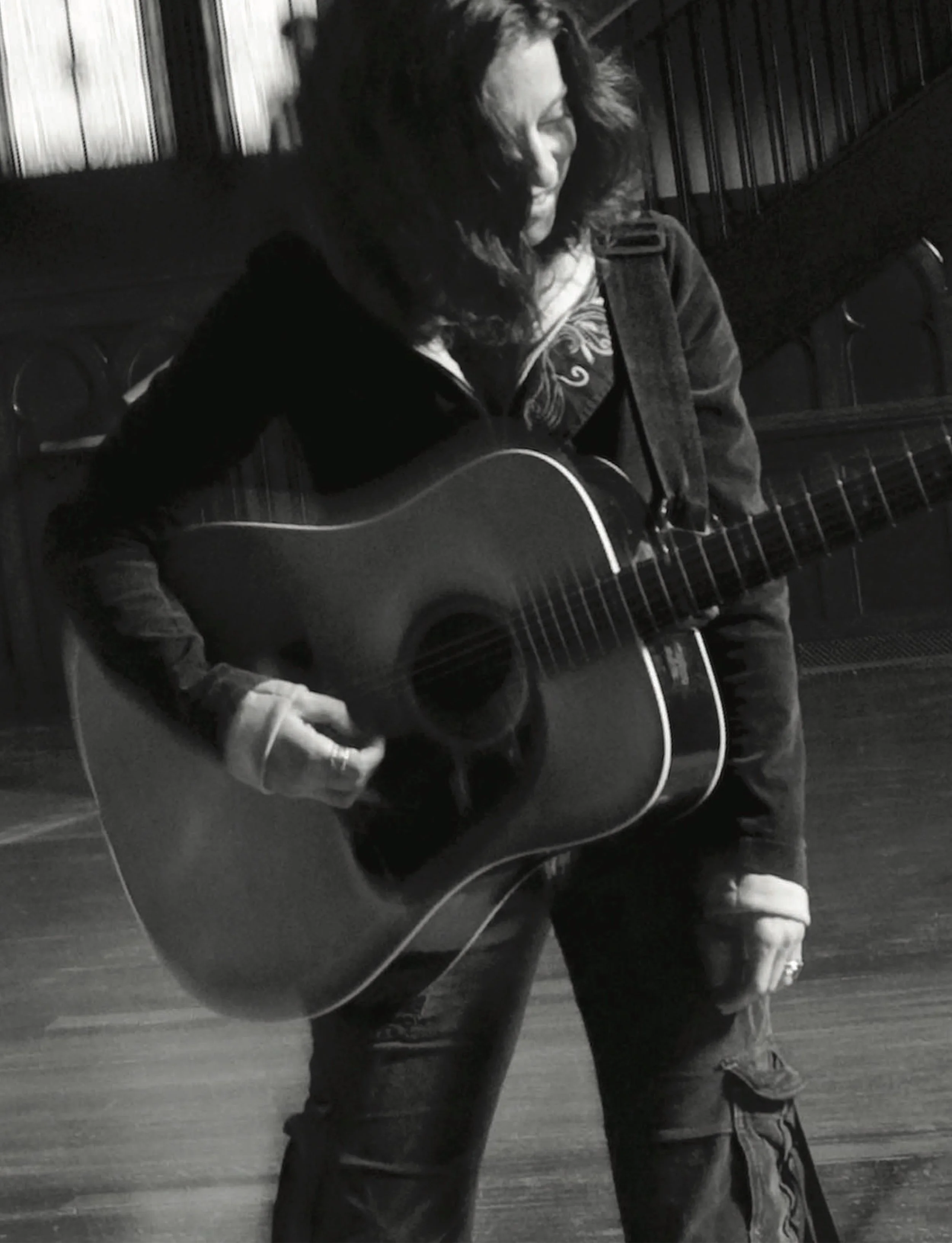

DiFranco has a bounce in her boots as she strides to the front of her tour bus, a Prevost X 3-45 VIP Entertainer, with her hands in the kangaroo pocket of a hoodie under a tour-worn denim jacket. She poses with the band: Eric Heywood (guitar and pedal steel), Todd Sickafoose (double bass), and Jharis Yokley (drums). At five-foot-two, the top of her head barely reaches the bottom of the Prevost’s windshield, which reflects the lowering Lake Erie sunset. She goofs for the camera, spinning around, making faces, cracking up the rest of the band, but the fading light pulls her attention toward the stage.

“We gotta go to work now,” she says–nicely–to cut short the shoot.

Minutes later, DiFranco emerges under blue lights, a shimmering rain of mallets on cymbals, and a cheer from the crowd that drowns out everything else. From underneath the cries of “We love you, Ani” emerges a track off her 2014 album Allergic to Water, the groovy “Still My Heart”–but louder, larger, lusher than the studio version.

“I’m so happy to be here,” she says–and she is, it’s easy to see that she means it. “Seeing the skyline, the breeze off the water …”

She’s joyful but also deadly serious–something that’s characterized DiFranco’s music from the beginning, sometimes bedeviling critics who want to reach for words like “protest” or “polemic.” After introducing the band, DiFranco slips into the soulful “Do Or Die,” off her 2021 record Revolutionary Love. This track borrows a Bill Withers groove as the backdrop for some of the most lapidary political lyrics that DiFranco’s pen has cut in years: she sings about the “sheetless KKK” on Pennsylvania Avenue, Yankee Doodle Dandy’s “doozy kind of carpentry” to fashion a ballot box that deceives. Still, the message is of urgent organization, grounded in belief:

Do you ever just wanna give up?

Well, me too.

Are you shocked by what people get

Get used to?

Do you wake up in a cold sweat?

Well, that’s sane.

Least you got a little brain left,

You got a little brain.

She urges the audience as she urges the song along, hiking her knee to tug at the band’s tempo, feathering and then slamming her foot into the wah-wah pedal, playing it like a trombone.

We can do this if we try,

If we do this like it’s do or die.

Coming up for air after the song, DiFranco admits to the audience something that she might have said at any point in the past forty years of making art and entertaining, from unpaid slots at Buffalo bars to headlining the biggest concert halls, all from a nation that keeps giving her and her fans the same battles, again and again.

“I’m feeling weirdly, strangely, inappropriately hopeful,” she says.

The rest of the set ranges widely over the material from those four decades’ years: songs from her latest album, Unprecedented Sh!t; from Revolutionary Love; several fan-favorites from Little Plastic Castle; and selections from Dilate and Not a Pretty Girl.

After accessing an even higher gear for “Pixie,” off 1998’s Little Plastic Castle, DiFranco acknowledges how much she’s changed over the years–“finally free of the Judaeo-Christian materialist thing,” she says. But she clearly has no problem slipping back into all her old selves. When she does, she brings with her hard-won wisdom and an ever-enlarging musical vocabulary. No longer the upstart folk singer freshly arrived in New York City from the southern crust of Canada, she’s earned a spot far above genre. Songs like “More or Less Free” might tempt comparisons to Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, or Woody Guthrie–and then songs like “New Bible” will remind that she can write like those poets, but she can swing like John Henry’s hammer, too.

Longtime fans like those gathered in Buffalo tonight know that Ani DiFranco has only ever been interested in being who she is–which is unprecedented, one minute to the next.

At the end of her set DiFranco bounces offstage. Her resting face is a smile, all teeth. She makes the audience wait barely a minute before charging back out for an encore.

Aidan: Ani, I saw you last at the Buffalo stop of your Unprecedented Shit tour, which was phenomenal. It was a beautiful night and it seemed like the crowd was entranced. How was the homecoming from your perspective?

Ani: It was really sweet. It was a very sweet homecoming. It had been a long time since I visited Buffalo, let alone played there. It just felt really good to see a lot of beloved people, friends that I have and have not met.

One thing that really struck me, both being in the crowd and also able to look out from backstage, was just how multi-generational the audience was. How are younger audience members finding you? Do they start with the really early work or are they sometimes encountering you for the first time with your more recent albums?

I think it happens every which way. Every person seems to find my music or something in it for them in their own way, in their own time.

Weirdly though, this multi-generational thing has been kind of a hallmark of my audience almost from the beginning. In the beginning the media certainly portrayed my audience very vehemently as other young women, angry young women, girls with hair on their legs and under their arms and not on their heads–which is, I guess, a description of myself. But, you know, at the time, I think that that hammering by the media went a long way to excluding people from my shows, people who might otherwise have found an inroad. They created a stereotype of me and my music. And they told people who was invited and who was not. I have felt along the way that I had to outlive that stereotype in order to be free to be myself and write songs and have them connect with whomever they might want to connect with. And I think that's basically the case between me and any given listener: we had to get around what the media was telling us to do or not do and just find our own way.

But remarkably people do that. People are able to follow their own hearts despite what they're being told. Pretty early on it might be a young woman coming with her father or her mother, or there might be people of all ages coming via different routes. Maybe this person's a guitar player and is just really interested in that aspect of what I'm doing. Or this person's a writer, or this person's a feminist, or this person's an activist. That's just something that I've always appreciated about my audience: when I look out and I see a diversity I feel proud that we all bucked the system and did what we felt like doing.

And that's also remarkable because the system itself has changed, right? It used to be that radio DJs were the mediators, telling you who you want to be listening to. Now it's algorithms that are just continuously feeding you stuff that it thinks that you'll like–and you found ways to get around both.

Yeah, that is certainly more and more of a thing, pushing people into echo chambers. I agree, it's becoming harder to resist being led.

I'm not super interested in genre or category except insofar as what it reveals about the categorizers. And one thing that I've always found interesting about the way you've been categorized is this relationship with folk and, early on, the label of anti-folk.

I think back in the 90s, that term was just an indicator that this is a new generation of people playing acoustic instruments and writing songs and interweaving political activism with music, making political art. I think that's a hallmark of folk music. When I was entering the scene in the early 90s, the folk scene sort of felt like it was dying off. You know, you go to folk festivals and nobody is under fifty years old, and it was not the hip genre of the day. Just the very term “folk music” indicated an older generation, a sort of a passe form or genre. I don't think there was any difference in the anti-folk people and the folk people other than their age. So it was really like an age indicator, but I think we were doing the same work with a slightly different uniform in a slightly different time period. But I did find that when I started showing up at folk festivals, the smart ones, the cool ones, the Pete Seegers or Odettas, there were so many that were welcoming to me. I came with a cadre of teenagers and they were like, yes, yes, bring the new blood. Many did recognize, she's one of us. She's one of ours. I always just called myself a folk singer. I never really felt the need to update that term or, you know, try to make it sound cooler. For me, folk singer is cool.

It feels like we're continuously seeing this play out around folk and maybe in a different way around jazz, these more tradition-based genres. The Bob Dylan movie dramatized this pretty well. Do you think that this is a cycle we'll just continue to see repeat? Are you seeing evidence of it now? Or is there a point at which we'll get past this young-and-old thing?

I don't know. I don't really spend too much time reflecting on popular movements or where is it going to go or trying to steer myself in an advantageous direction or anything. “Americana” is the latest term for people playing acoustic or song-based music that sounds hipper than folk. Maybe each generation wants their own language to describe themselves, and that's probably natural and cool. But underneath it is the through line. I certainly hope that these, like you say, more traditional forms of music don't go anywhere. Like jazz: where else do you find the playing of instruments and the pursuit of that really being able to speak full sentences, paragraphs, share novels of human experience through a musical instrument? That is something that new generations with their computers and all the more technological tools available, it's not an emphasis. So, man, I sure do hope that the playing of instruments never gets gone. And I think of folk music in a similar way. There's something central about writing, about poetry, about storytelling, about sharing and keeping alive the people's history through oral tradition. I think that also is maybe not an emphasis of modern music or pop music–never has been. I hope that that tradition doesn't ever go by the way either, because that's another important aspect of the human soul that is carried through that genre.

Speaking of through lines, you've covered a lot of sonic ground across your albums–total reinventions in terms of approaches to production, arrangements, genre influences. But one thing that has felt fairly consistent across all of your work is your totally distinctive style of guitar playing.

People have remarked over the years about the dynamics in my music. And I think that's just my personal taste–my soul kind of glazes over with a wall of sound. What really excites me and attracts me is to hear the silences up against the sounds, to have contrast and to leave room for the music to breathe.

So, take people strumming guitars, which was a very common way to approach an acoustic guitar–to strum it, that just fills in all the space. There's no more air around the music and inside it and moving through it. That just didn't feel right to me. I wanted the sound of my instrument to have breath, to have a pulse. So I didn't use a pick and strum, I used my fingers, finger-picking style. And I instinctively did a lot of grabbing and muting, so that there was always that contrast between sound and silence. And with those contrasts and five picks instead of one, you can make incredible rhythmic patterns and you can syncopate the relationship between sound and silence and manipulate those syncopations to rests. It's so manipulable when you're finger-picking and you're conscious of the shape of notes and the space in between them on some subconscious level.

But also it was a fucking survival technique. I started playing in bars as a teenager, Nietzsche's, the Essex Street Pub, etc. Just standing in the corner of a bar, surrounded by people who are not inherently interested in who you are, what you have to say, or the fact that you're pouring your little heart out in your little songs. They're trying to take a load off. They're trying to hook up with somebody. And I guess I felt like I had to devise ways to capture their attention or just drown, just drown in a sea of existential dread. If you spank your strings really hard and then you cut off the sound and you leave a gaping hole, somebody talking over your music will suddenly hear their voice really loud. It's as simple as that. And they'll go, shit. And they'll turn. And in that precise moment, you have an opportunity to interest them in what you're doing.

And I do love being in the moment on stage and improvising to the extent that I'm capable of. I'm not really a sophisticated player in terms of soloing and stuff like that. But I am very much connected with the jazz tradition in that it's always got to be in the moment. Playing parts is just numbing.

Picturing you in Nietzsche’s and the Essex Street Pub makes me reflect that the places you live show up in your songs in sometimes specific ways–like talking about your uncle losing his job at the Trico plant or being in New York looking across the water to New Jersey. I'm curious about the move to New Orleans and how that may have started to show up in your music.

Yeah, New Orleans is just a vast new musical landscape for me. I came here for the first time when I was very young, just kind of driving through, but then I came to play Jazz Fest here in New Orleans in the late 90s. And I was just like, holy shit, this is just happening down here? I mean New Orleans itself and the depth and breadth of the musical traditions and explorations and manifestations and what on every street corner and any given Tuesday is just happening in New Orleans. So I immediately was like, I need to spend more time here, which I started doing. I was just drawn. And not just to the music, but to the culture in general here, which is very human, very open. It's almost like a lot of the veils are lifted. A lot of the constriction–of whatever uptight, Puritan American codes of conduct are just gone here. It feels less like America than any place else I've been in America and more like someplace where that's not standing in between people as much. And maybe the veils are lifted by alcohol. Certainly this is a drinking town, a partying town, but I think it's deeper than that. I think this is a place that has a deep, long-standing tradition of being free and being fully embodied in a way that you don't see everywhere in America. Certainly these traditions were largely built by African Americans, by enslaved peoples who had to work really hard to feel free, to liberate themselves within their bodies, to find those ways of transcending circumstance. So I think it's embedded deep in this global musical epicenter–where jazz comes from. And so many of the American musical traditions can trace themselves to the mouth of the Mississippi. I think it just pervades, this power of being able to transcend it all, of being able to lift yourself above everything–it’s still moving through the culture down here. I love it. I think there's certain people, types of people that when they come to New Orleans, they just don't wanna leave. I'm one, I guess.

There's also a great writing tradition there. I heard you talking about writing your memoir and how that creative process was different from songwriting. I think you said something about needing to spend time sitting in silence and waiting for things to come back to you. That sounded like that wasn't how you write songs. Did the experience of sitting down and writing a book change your approach to songwriting at all?

Maybe it did. I would say, first of all, it made me more grateful to be a songwriter. The book I've described as like whittling. It's like, God, just sitting there hour after hour whittling, or carving a slab of stone trying to make a shape.

The older I get, the more clearly I understand art in general. And I understand my songwriting as being collaborative–I feel I'm gifted by spirits, that I'm collaborating across the veil, that I'm guided. With songwriting it's much more apparent, because I'm hanging out with my guitar and I just sort of go into a space that's not fully conscious, perhaps, and something comes through. And it takes a lot of work on my part, I have to participate with it, but it's not done alone. The book writing, it was harder to find those moments where something is coming through, because it was like just one moment after another of whittling. Maybe I was more on my own in that process, because it was so long and painstaking to put one complete sentence after another for hundreds of pages.

I think maybe it increased my patience level. Patience is something I've not had a lot of in life or in my work. I think when I look back on my songs, I can see the places and the moments where I copped out, where I was too impatient and I wanted to be done and move on to the next song or the next thing. Like, ugh, enough of this. Whereas if I had had the patience to let it incubate, percolate, you know, I might've had a stronger song. It's like that third verse, I copped out on the third verse, I just wanted to be done, or something like that. So I think patience is an ingredient that I'm employing more, in the way I work now, and the book writing probably also influenced that.

I just got chills, because my wife Rachelle’s always telling me to be more patient with my writing and wait to make it perfect. That makes me think, though, as we just marked the thirtieth anniversary of Not a Pretty Girl, you were incredibly prolific in the 90s, putting out an album every year, which means we're in this period of having all these thirtieth anniversaries of these awesome albums and you have to spend time with those older works. I'm curious what that's been like for you. I know you play songs differently in the moment when you're doing them live. Have you ever felt compelled to change them more dramatically, to actually rewrite verses or things like that?

Yeah, sure. When I play old songs, I mean, even newer ones, I will change them on stage. Like, that verse bugs me and I'll just go ahead and change it and sing it a different way. And some of them I don't even know. Because I don't listen to my old shit at all. I don't listen to anything me, if I can help it. But sometimes there is occasion to, and I will suddenly be confronted with the original recording and go, shit, that's how that goes. Oopsie. I’ve been playing it wrong for the last twenty years for some reason.

There are some songs that people sing along with, like “32 Flavors.” Most audiences sort of sing the chorus wrong in a certain way that I won't try to describe, but wrong. Recently, I've been thinking, wow, I need to go listen to that recording because maybe I'm wrong. Because they all seem unanimous in how they're singing this and I don't even know anymore, you know?

But just to play devil's advocate about your impatience with your own writing, Aidan. Not only did I cop out on some third verses or whatever because I was too impatient–every fricking recording, every album that I made was a study in impatience. I did them on my own pretty much, I worked with whatever studio guy was there in the studio to record it and then I mixed it myself and released it myself. I just didn't have the time in my own perception. I just couldn't stand the process of trying to find the team of experts to make it all sound right. That was not interesting to me. When I listen back to most of the records I've ever made, what I hear is, they could all be better. They could all sound better. But for me it was like, that's fine. And I'm moving on to the next thing. So here's my devil's advocate and my support of you and your impatience. They connected. They connected. Were they recorded, mixed, and produced as effectively as they could have been to reach the broadest audience? No, they were not. They were not. But they reached the people that needed it the most. And those people carried me here. And we carried each other. Somehow, even though it all could have been better. I could use a drop of the perfectionist, because I'm like the opposite. I'm a that's-good-enough-ist. Like I-don't-give-a-fuck-ist. But somehow it connects. And if it's coming from someplace really deep inside you, even the fact that you sort of sped up and went around that one roadblock, still people can feel where you're coming from and they can get in there and relate to it and find what they need in there. I don't go out of my way, unfortunately, to support myself through it all, but I can support you and say that maybe perfectionism isn't always the best thing. Maybe, just getting it out there, pushing it into the world and seeing where it sticks and who picks it up and following the process that way is just as legit.

I was thinking about something I felt is maybe another through line in your work and seems to be more explicit in your most recent music–a kind of desire to get past concepts of things to allow yourself to have encounters with the things themselves. I hear this with “The Knowing” and “The Thing At Hand.” I felt like perhaps that was a desire that was latent in the earlier work, maybe not expressed with the same kind of directness. But in the newer work it almost has a kind of Buddhist sensibility to it.

You are not off base, you're listening. And I appreciate that. You're not just listening, but hearing. I played a part in the culture of identity politics, which I think is a very important evolutionary process for, I'll just say, American culture. In the 70s, I grew up in the dawning of identity politics where people who are not privileged white males, for instance, are saying, I'm here too. I have a different perspective. Here is my perspective. Can this nation and this culture really be inclusive and diverse? Can we really celebrate and harness the power of our diversity in America, which defines us? Or will it continue to be sort of on paper only? I think this whole process of people, of the whole huge majority of the world designated under “other” coming forward saying what it is from their point of view, finding each other, finding their identity in a self-defined way, not defined from the outside, finding all of these things, insisting on inclusion, you know, that was very much a part of my mission, to elbow out space for myself on my own terms within the culture. And that was happening on many, many, many fronts. Again, like I say, it's such an important process to have everybody be included and have everybody heard in the chorus. But at this point in my life, I think I have fully entered another phase of my mission and I don't know if I can define it well. I've gone beyond identity within myself. In fact, I'm fully immersed now in … I want to say the truth. What for me is my new truth is that these identities, these roles that we're playing, these names and stories that we invest ourselves in so fully are all a mirage. The spirit that lives in me that's manifesting extremely temporarily as Ani and you as Aidan–that’s what we really are. And it is eternal, whereas the identity, the name, the story, the hierarchies, relationship of identity to another identity, the power, all of that is an illusion.

I was asked to make a children's book and that's where the song “The Knowing” comes from. It's also in a book form. When I thought, okay, what book do I want to make for kids? That was what pulled me. I want to talk to kids, who I think are still inherently more connected with their spirit and the spirit that lives in other beings and less knowledgeable, let alone ingratiated into this idea of you being a white male, blah, blah, blah, all the descriptors, all the adjectives, all the labels, all the identities and all the politics. This, beautifully, is not a part of a young child's world. They have to be drawn into these systems of identity. So, I was thinking, gee, if I was going to connect with young kids, I would want to affirm that thing that I think is more alive in them potentially than any of us, where they don't see that, the surface of identity. They see through that, spirit to spirit.

And that’s not to say no to identity. I wanted “The Knowing” to be a “yes and.” Like it's so important to know where you come from and who you are and what the context of this journey and your life is and who your community, who your family, who your friends are, to find a place in the world and to be able to define that–that is cool. But ... maybe you know that and know you're more than that, you're more than everything that everyone will ever describe you as. Every adjective, every label that will ever be leveled upon you, you are more than all of it. And you exist also in a realm beyond all of it.

That's all I'm working for now, which is interesting. You know, I spend my life trying to affirm people in their identities and their lives and their experiences. And yet I'm also really deeply in this tension of–okay, but none of that's actually real.

I feel like there's also an essential tension that I'm living and working through with all of my art, in which language is a liberating force and also the cage. And those things are related, what I was just talking about. I work through language, but I work to liberate us from language.

That makes sense. That's a beautiful answer. It is interesting knowing that that song, “The Knowing,” started in the context of a children's book. But also I feel like I'm hearing a similarity in the way you're talking about the self and identity as immersive. It sounds a lot like the way you were describing being in New Orleans.

Yeah, I mean, sure, I think it's related to that part of what we were talking about, that simply put, this is a city where people seem to find a way to look through all the identifiers and relate to each other spirit to spirit to transcend all of the things that put us into places and supposedly define how we're supposed to relate to each other, and that people cut through that here through music or through whatever. They find ways to each other, spirit to spirit, that cuts through it all.

in print