celebrate oxford pennant

Makers of nostalgic pennants, flags, banners, and more, Buffalo’s Oxford Pennant will be moving its operations to Larkinville in the spring of 2026. For now, it lives downtown at 810 Main Street in a four-story building so quaint that it evokes an HO-scale miniature. The storefront windows have been covered with a colorful, modernist pattern of blank flags, pennants and banners, effectively hiding the contents of the building from the public eye. The building also gives artisanal dessert vibes. Bundt-cake-orange brick, biscuit-colored columns and cornices, blueberry accents, and clean typography–it’s a midcentury cookie tin. A movie theater box of candy. I want to eat it.

The front door opens directly into the order fulfillment department where industrious workers scuttle into place while an orchestra vamps. The lights dim and a spotlight follows a young man with purple hair and facial piercings as he walks up a staircase of corrugated boxes to a long, glossy table, strewn with shipping labels. He sings into his tape dispenser.

“Flags and banners and ampersand. / We ship our wares all over the land.”

Symmetrically flanking the table, two workers in hoodies pirouette into a massive roll of bubble wrap. Another makes it rain packing peanuts. The song continues.

“Call it team spirit, not braggadocio. / Rah-rah-rah, go team, go!”

The band kicks into high gear, and the kid scissor leaps into a box of pennants. Perfectly cued by a blast of brass, four workers somersault out of cardboard boxes and launch into an impressive series of aerial cartwheels. A giant banner unfurls from above: “Welcome to Oxford Pennant!”

Okay, that didn’t happen, but it feels like it could have. The story of Oxford Pennant is often surprising and improbable.

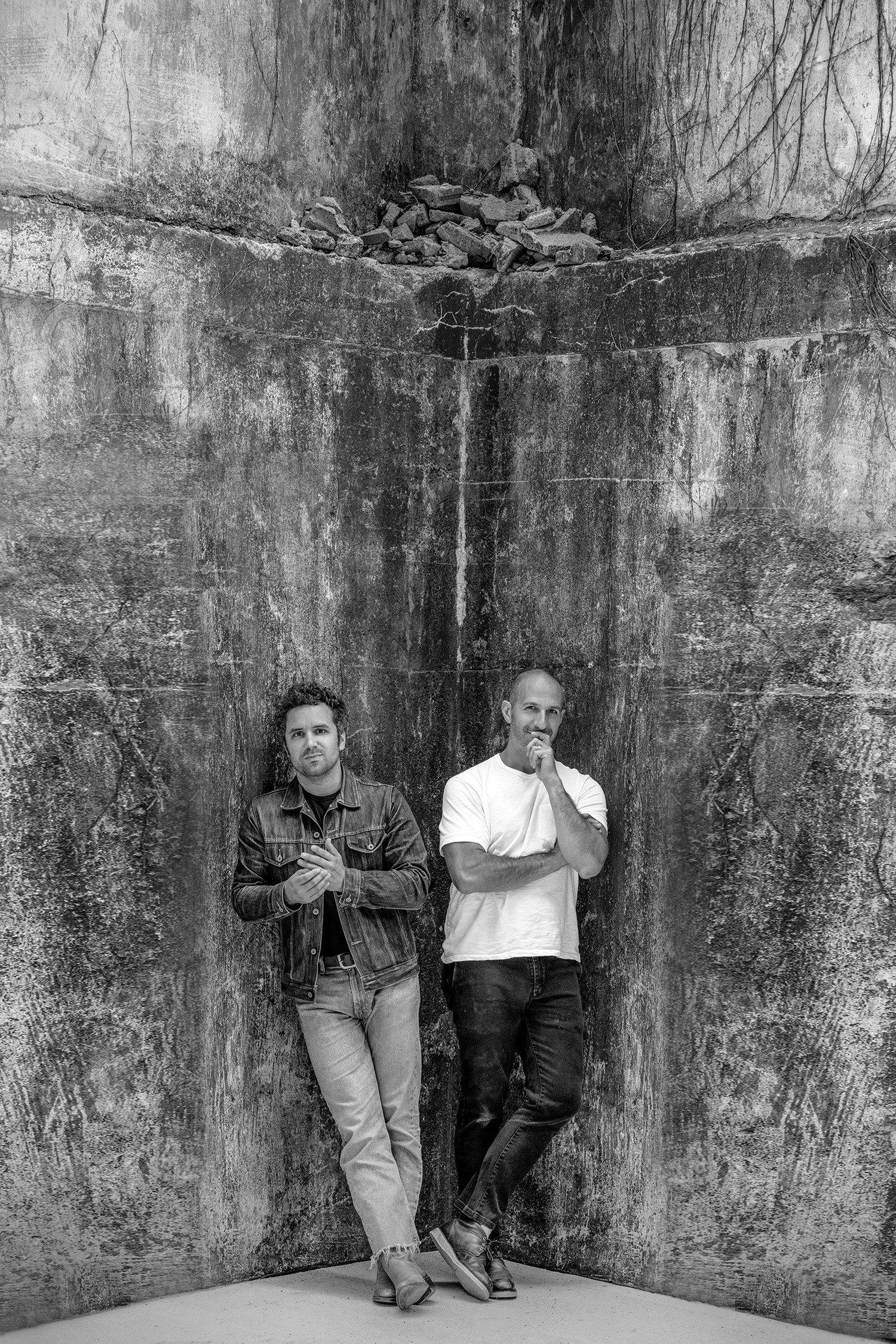

Take the nature of the product itself. Oxford Pennant makes and sells wool felt pennants, banners, and “camp flags,” a term that founders Dave Horesh and Brett Mikoll had to coin themselves because they couldn’t find evidence of a historical name. The idea of a summer camp flag is like something out of a Charlie Brown cartoon. It’s niche and nostalgic enough to inspire a Wes Anderson movie. There is no felt pennant industry to speak of today. It’s an archaic product, a relic from a time when silk screened T-shirts did not exist because everyone was too busy being well-dressed in tailor-made suits and dresses. A twenty-first century business that makes and sells felt pennants and banners is not as improbable as one that, say, makes and sells Davy Crockett hats, but it’s also not that far off.

m. dellas

Then there’s the quality of the products. In an era abundant with disposable swag at sweatshop prices, Oxford’s pennants, banners, and flags are made from real wool, not synthetic fibers. All the materials are purchased from domestic suppliers. Elements affixed to their products, such as letters and borders, are sewn on individually by a real Buffalonian operating a sewing machine in a comfortable, well-lit room. Silk-screening is also done in-house and by hand. Grommets are etched with the company name. Everything they produce is of a build quality we’d expect from the early-to-mid twentieth century. The design–consistently clean and often with an understated charm that cleverly captures the look of previous eras–is also done in-house by local talent. Horesh and Mikoll could have easily outsourced the work and cut corners on materials to increase their profit margin. It is practically expected of business owners today. Improbably, they made an impressively designed and assembled product. Get an Oxford Pennant banner up close. You’ll see what I mean.

Also surprising and improbable is this incomplete list of their past and present partnerships and clients: Adidas, Aerosmith, Andrew Bird, Blink 182, The Buffalo Bills, Disney, Def Leppard, Fall Out Boy, General Motors, Silvan Esso, Gibson, Hamilton, J Crew, Jason Isbell, Elton John, The Lemonheads, Joni Mitchell, Mumford and Sons, Muscle Shoals, My Chemical Romance, My Morning Jacket, Willie Nelson, Nike, John Prine, The Rolling Stones, Sesame Street, Shopify, Star Wars, Billy Strings, System of a Down, Urban Outfitters, Weezer, and Wilco.

In 2021, they had a forty-foot by thirteen-foot “Let’s Go Buffalo” pennant hung at the top of Buffalo’s tallest building. C’mon, now.

Then there’s the improbability of the company itself. When I spoke with Horesh and Mikoll, everything sounded like a happy accident, from the way they met (randomly assigned to travel together on a business trip), to the name of the company (Horesh’s rescue dog simply arrived with the name), to the very inception of the business itself (Horesh “needed a product to sell”; it was a “side hustle”; they did it for beer money, and so forth). The serendipity of it all, however, should not belie their passion. If they simply fell into this business, they fell hard. Acutely aware of the historical legacy they’ve invited into their lives, Horesh told me, “We want to be the preeminent brand associated with this American-like heritage.” They are.

That legacy is actually no stranger to Buffalo. The DeMar Manufacturing Company, founded in 1911 and located at 109 Oak and later at 270 North Division, made wool felt pennants until their closure during the Great Depression. Trench Manufacturing, which operated from 1929 to 1995 had four different locations in Buffalo over the years, one of them less than a mile away from Oxford Pennant’s current location. At their height, Trench was actually the largest manufacturer of pennants in the country. That industry dominance might have had something to do with the fact that Sportservice, the company that supplied ballpark concession stands across the country, was also located in Buffalo. This city, as every citizen is made to understand in one way or another, used to be somebody.

Maybe our late-twentieth-century fall from grace explains why so many Buffalonians tend towards nostalgia. To an extent, Mikoll is one of them. I qualify that speculation because there’s so many ways in which he and the Oxford team are forward looking. (More on that later.) Framed vintage pennants adorn the walls of Oxford’s headquarters, and they have a large inventory of antique ephemera to be used as design references for their product. A significant piece of the Oxford origin story is Mikoll’s pastime of going to estate sales and thrift stores, noting that they are “pretty much the only place[s] you can go for free and still be entertained.” These spaces are not unlike museums, places where we could look at the ordinary objects of life before we were born. Pennants are one of those objects. “The more you expose yourself to the product,” he tells me, “you see the repeating typefaces, the repeating imagery.” He sees what they’re doing as “paying homage” to this tradition. “We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel every time. Why try to renovate something that somebody has an emotional connection to?” Horesh: “What could be done differently? It’s been done perfectly for 150 years.”

Widely studied, commodified, and politicized, nostalgia is a word that comes from the Greek words nóstos and álgos: homecoming and ache, respectively. This pain of not being able to go home is often determined by the one-way trajectory of time. We can’t get there from here. Sometimes, however, this ache comes from the fact that the home we seek never existed in the first place. It’s a fantasy, a version of the past idealized to the point of deceit. In an episode of University of Denver’s podcast RadioEd, Dr. Ana Babic Rosario, an Associate Professor of Marketing at the University, says, “When consumers are feeling bad about themselves personally or about our society, they tend to look to the past and that’s where nostalgia marketing will be really effective.”

We are living through an era of peak bad feelings.

She goes on to say that nostalgia allows people to “feel like they are regaining a sense of power and a sense of control by indulging in the past, but this could be counterproductive, and it could actually be stifling progress.” Perhaps this can help us better understand the seemingly endless parade of Hollywood remakes and throwback packaging as well as the political sloganism that suggests life was better (or, ahem, greater) in some previous era. In Buffalo, we may vicariously long for a version of our home informed by black and white media that depicts a bustling downtown with theater marquees, thriving shops, and rail cars that run on streets beyond Main, but it’s a home that now exists solely in our imaginations, conveniently ignoring all the ways in which the present is safer and more equitable.

Recent studies also suggest that cold weather makes people more nostalgic, so there’s that, too.

Nostalgia stimulates the brain’s reward center, the place where addiction lives. This is no secret to multi-billion-dollar-global-media-mega-conglomerate Disney, who, it could be argued, no longer trades in cartoon mice but neurochemicals. Like gunpowder, nostalgia is powerful enough to launch a bottle rocket in the air or put a bullet through the brain. It dazzles as well as it deludes.

This all makes me wary of nostalgia, but I have felt its pull all my life and still somehow managed to look forward. I think of all the scrappy, progressive, queer, punk bands who appropriate vintage sounds and styles to argue for a more egalitarian future. I’m convinced there’s a way to harness nostalgia’s power for good. Has Oxford Pennant found it?

Their slogan is “Celebrate Everything.” But everything everything? Horesh: “We’ve always said nothing racist, nothing sexist, nothing political. [...] Some would argue that messages of unity are political. I don’t feel that way. Neither does Brett.” And when someone tries to call them out for marching in Buffalo’s annual Pride Parade? Horesh offers them an explicit, two-word directive.

“Acceptance? Unity? Who says no to that?”

The current Google Street View image of Oxford Pennant’s 810 Main Street location reveals two men standing outside the building–two men who look suspiciously like Horesh and Mikoll. I almost ask them about this, but I don’t because I want to believe it’s them. Per Google policy, they’re blurred out, but this much is clear: one of them is giving us a thumbs up, the other is giving us the finger. It’s an image that tracks. Their company feels like a postmodern Disney–highly engineered joy in a tightly controlled environment with a sly, knowing wink. When their website refers to Downtown Buffalo as “the happiest place on earth,” I can almost hear one of them whisper through gritted teeth, “fight me.” They’re friendly and warm, abundant with good guy vibes, but Horesh has a handshake that could turn bone to rubble. He’s an intense man of strong conviction, the kind of man who might, hypothetically, give the Google Street View car the finger. Oxford Pennant is a cardigan sweater that is equal parts Mister Rogers and Kurt Cobain.

Both Horesh and Mikoll admirably lean into their values, even if there’s a financial cost. I’ve heard both of them say in different contexts: “We answer to no one but ourselves.” When I ask about growth, Horesh is cautious: “Growth is fraught. [...] When you talk to people who are in the business of growth–venture capitalists, politicians–the only thing they ever want to know is like, well, how much money are you gonna make, man?” Horesh understands that they’ve built something wonderful and profitable, and sudden changes could jeopardize that, but he also seems refreshingly more concerned with happiness–of his staff, and his customers, and his own.

“This point of view, this philosophy has created what I think is a really wonderful life for the people that are here. It’s a very civil, happy place. I think you can see that in the people that are here–they dress how they want, they play the music that they want, everybody gets to be who they are here.”

Indeed, the entire workforce was warm and friendly during my visit. I noticed a whiteboard in the hallway with staff music recommendations. (How nice!) A room of well-paid, diverse workers making friendly small talk with their bosses? It felt like a page out of Richard Scarry’s Busytown. I craned my neck to see if a cat in overalls was running one of the sewing machines.

Horesh is not afraid to be sincere: “When I look at my beautiful wife, and my beautiful children, in the city that I love, working with my best friend, working with young, creative people who want to build this thing with me–I feel like I’ve unlocked a secret. It makes me feel like a million bucks every day. I mean, I really do. I wake up every day excited to see what the day has in store for me.”

When I ask him why that attitude feels like such a luxury, he gets philosophical: “Why is that attitude a luxury? Because the only way you can have it is if you make peace with being uncomfortable. It’s a really hard thing for most people to do. This is an incredibly uncomfortable company all the time. I just find peace within the discomfort. You know, the plane has turbulence and you’re still finding a way to get your rest.”

Comfort Is a Slow Death, says one of their Oxford Original camp flags.

In the best of ways, Oxford Originals, the line of products that feature their own sayings and mottos, are pithy and playful. Largely written by Mikoll, they seize the storytelling opportunities of the medium. Mikoll, a veteran of the Buffalo music scene, appreciates the poetic tension of words on a flag. No ordinary canvas, flags are for warnings and declarations. They are weighty icons charged with history. But what happens when a flag says, “You’ll Think of Something,” or “Every Damn Day,” or “Who The Fuck Are They and Who Cares What They Think?”

Like Jenny Holzer’s Truisms, Mikoll’s flags often back us into a corner, confronting us with ideas that beg us to agree or disagree. In doing so, we participate in an act of definition, outlining our view of the world. Yes, we tell ourselves, looking at the flag, I agree: Nobody Wins Unless Everybody Wins. Or Nobody Knows Anything? No, I don’t think that’s true.

My favorite Oxford Original camp flag: Great Minds Overthink Alike. Or wait, maybe it’s Give a Damn. I’ll have to overthink about it.

Horesh and Mikoll willingly–celebratorily–participate in capitalism, running a profitable business that employs over forty people. Since the summer of 2025, they’ve been running three eight-hour shifts a day, five days a week. But throughout our conversation it repeatedly felt like moneymaking was the fringe benefit to what they’re actually making: Oxford Pennant. There’s a photo studio on premise, where all the website images are taken. In part, it’s further evidence of the tight control they exercise on the business, but when you’re in the room, looking at a few fake walls and model furniture ready to be rearranged to look like a real living room or bedroom, you realize that you’re looking at a theater set. A paper moon sailing over a cardboard sea that they occasionally bring to life. In so many ways, their work looks like play, like an elaborate game of make believe. The right kind of nostalgia.

Repeatedly referring to each other as best friends during our conversation, Horesh and Mikoll even once compared their relationship to a marriage. Together, they’ve built a product with instant appeal and infinite application. “We’re very ambitious and we have ideas,” Horesh says, “but I’m not driven at all in any way by trying to win the game.” In the climate of corporate mergers and exponential expansion, this feels like a radical idea, but it’s actually one that, at least instinctively, harkens back to a simpler time, one where companies could co-exist, sell an honest product, and pay their employees an honest living. This is what that sugar-cookie HO-scale miniature on 810 Main Street invokes. I can’t wait to see what they do in Larkinville.

Industrialization and modernity may have set us on a path of increasing alienation. A gentle tug backwards, or homewards, could be healthy if it reminds us of what worked, so that we can, on our forward march, decide what is worth preserving. This was the power of the “Together We Will See It Through” camp flags that Oxford released at the height of the COVID pandemic. Based on a flag from the early-twentieth century, it reminded us that we’ve seen hard times before, and the answers lie on the horizon.