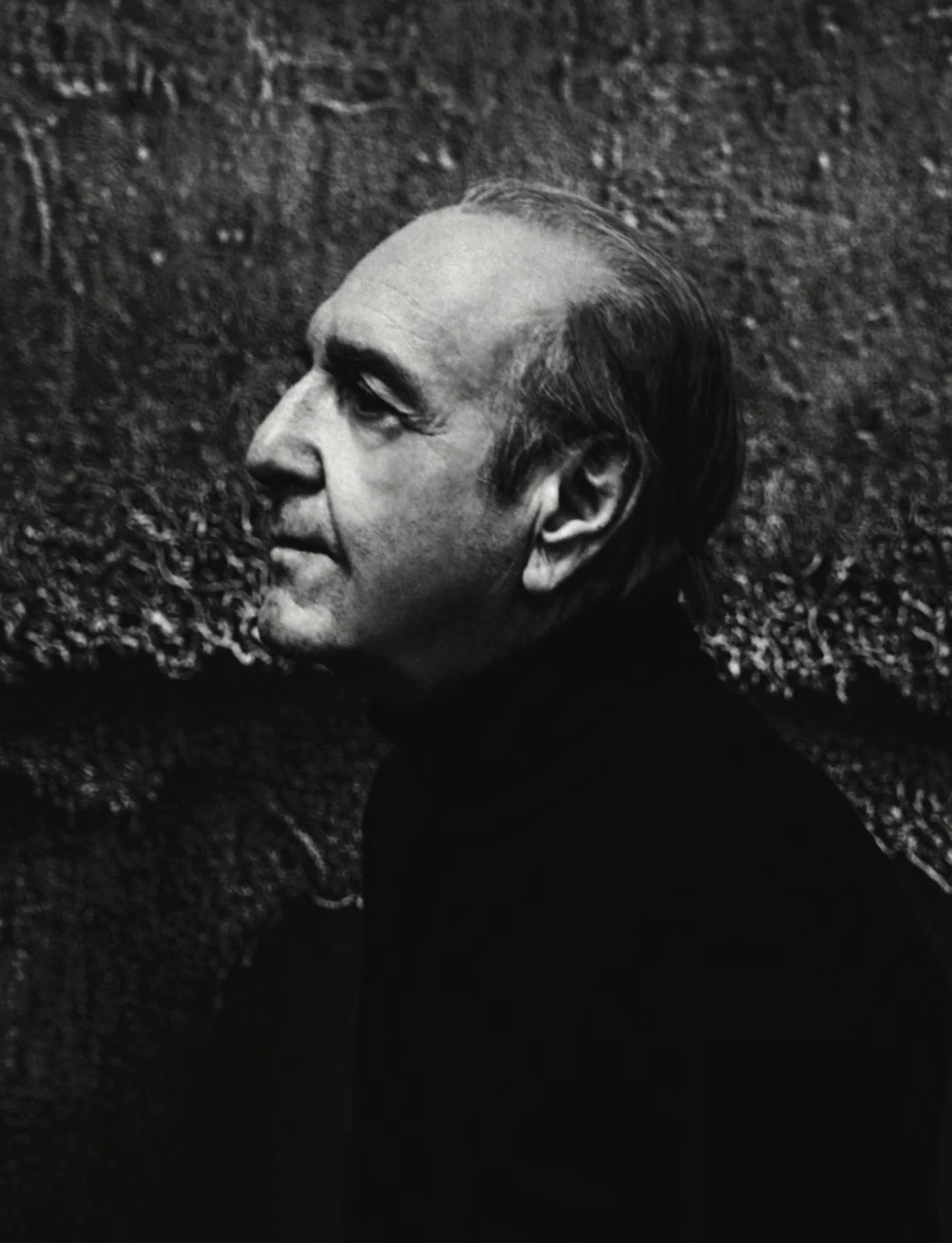

william maggio

When William C. Maggio retired in 1995 from a thirty-six-year career teaching fine art to high school students, his mission was clear: he would devote himself full-time to developing his own visual arts practice and end his side gig as a jazz pianist that had supplemented his family’s income for decades. His four sons had by then reached adulthood and left the family home in which Maggio has now lived for more than sixty years. This period of transition would be punctuated in 1997 by a life-changing near-death experience that clarified the direction and purpose of his artistic investigations while providing a profound thematic touchstone for his future course.

While the period of 1995 to 2000 is the fulcrum about which Maggio’s life and career as an artist turns, his prior training in the foundations of fine art, the decades he spent nurturing his family and generations of Western New York students, and his consistent engagement with contemporary art (and music) throughout his professional life are all critical to fully appreciating the artist Maggio has become and the intentions of his mature work. As Maggio himself says, “Nothing is forgotten, but one thing leads to another. I have never experienced a block, going way back. Even though the imagery has gone from realism to abstraction, there is a connection–in the application, the thought process–the connections are very obvious to me. I can see similarities between something I did thirty or forty years ago and what I am doing today, how I got here.”

At the time of Maggio’s formal education in the late 1950s, drawing was still the basis for fine art pedagogy. “I worked a lot with portraits, figure drawing, carbon pencil, graphite, charcoal. I was learning so much. I graduated from Buff State with a degree in art education in 1960, when there were so many great teachers there. It was a real art school.” Both by training and natural talent, Maggio is first and foremost a draftsman, and his mastery of the medium is powerfully evident across his early works. The Sextions series (c. 1975-1980), in which realist figures emerge from the surface amidst deftly shaded faceted sections, organic abstract marks, and seemingly liquid erasures, demonstrates his appreciation for the work of Francis Bacon (1909-1992), of whom Maggio comments, “The portraits on portraits, the double images capturing the changing positions of the figures. Whatever he touches it’s right. I spent a lot of time looking at his work.”

Maggio also mentions other artists whose repetition of fragmented figures and portraits floating in space provide a closer source of inspiration: “I liked Larry Rivers (1923-2002)–his Dutch Masters series. And he was a saxophone player, too, a musician, as well. I never thought he got the recognition he deserved. That was right out of college, back in the 60s, early 70s.” Indeed, several works from Maggio’s later Orator series (c. 1970-1975) appear in direct dialogue with Rivers’ Dutch Masters works. Maggio continues, “Rauschenberg was another big influence. I love [his] work. When I was in college, every year we’d go to New York City for a week and walk the galleries and museums, and I saw his work at MoMA, and there were also reproductions in art magazines.” But in a telling clarification, Maggio states, “Rauschenberg’s later work–when he really got into lithography and printmaking–I prefer his earlier work [the so-called ‘combine paintings’ that collage disparate elements onto the surface]. I don’t usually like collage, but everything here is so perfect.” Maggio would later incorporate vent grilles, rusted car parts, and similar found objects into his own surfaces.

Maggio reiterates, “I never cared much for collage; the actual thing that intrigued me was the billboard. I could see them becoming passé. What was so interesting about this work was seeing the decay.” Although he was not aware of the “Affichistes”–French and Italian artists like Jacques Villeglé (1926-2022), Raymond Hains (1926-2005), and Mimmo Rotella (1918-2006), whose works of the 1950s through the 1970s deploy torn billboard fragments in semi-abstract, but necessarily Pop-inflected compositions–Maggio’s Billboards series (c. 1996-2000) presents an extended parallel study, albeit one in which Maggio’s consummate draftsmanship and exquisite renderings of his by-then signature coil forms continue to reign.

Now as then, Maggio works in series. “I tried a lot of techniques, and experimented an awful lot, and I always liked to work in series,” he says. “I never understood how one painting–if an artist had an idea and he wanted it to be conveyed, how it could be done in one painting. I have to do a series, and with each piece the essence is more apparent. A lot of times I go back when I have similar thought processes; for example, I just did another in the series The Other Side” (begun in 1997). Maggio’s practice of moving backwards and forwards among different series complicates the process of dating works he failed to date at the time of their execution, but it also reveals his method of progressive knowledge accretion and refinement.

Like works in the Billboards series, those in the Coils, Slate, and Wallscapes series–the latter taking us up to c. 2000–represent the full flourishing of Maggio’s seductive drawing capabilities. The best of these works, beautifully poised between abstraction and representation and bodied forth with enchanting nuance, remind one of Jasper Johns’ (b. 1930) works on paper–the tally marks, the letters of script and stencil, and the continuing fragmentation of imagery. Maggio was particularly interested in Johns’ use of stencils, his own use of which is apparent in these series, and Maggio recognizes the relationship between his crisp representational fragments and the work of a sign painter like Pop artist James Rosenquist. But in this discussion of sources and affinities, Maggio’s appreciation quickly turns to the greater influence of his friend, colleague, and once housemate, Joseph Piccillo (1937-2022). “Joe was a sign painter, it was his skill, he’d gone to Tech High School. He opened up a little shop on Connecticut Street that was attached to the lot where his father had a service station, and there he painted signs for the local merchants. He was a master letterer–I used to go there just to watch him work–and he incorporated that into his early works. They were just stunning to look at. We were in the same studio space for seven, eight years. We were in the same school in Buffalo teaching art across the hall from each other, and I lived upstairs from him, so we spent an awful lot of time together.” Indeed, Maggio also mentioned an interest in the work of Robert Longo (b. 1953), whom Piccillo taught his draftsman’s craft.

Piccillo also inspired Maggio with his routines of daily life. “I always admired Joe’s commitment. Joe was the most, how do I want to say this–you could set your clock by his actions and movements. He had routines, like clockwork, and I realized then that if I’m going to do anything in art–I was torn between music and painting–and I said I can’t do this forever, but I needed it for the income. I decided early on that when I could retire, much as I love teaching and love these kids, if I’m healthy enough and I retire as soon as I can, I have maybe another thirty, thirty-five years [to focus and develop].”

Although Maggio’s later works–including and beyond his 1995-2000 transition–might at first glance seem unrelated to earlier works, the continuity of development that is so clear in the artist’s mind is indeed evident to the viewer who is able to take in the whole of his work. In terms of medium, technique, and subject matter, one thing does indeed lead to another. Regarding the shift from drawing to painting, Maggio says, “I was working on three-ply Strathmore Paper, and I couldn’t stop myself from wanting to dig into the paper. I moved on to something more substantial and carried over precisely what I was doing onto a stronger support, [Masonite panels and eventually] canvas stretched over wood panels.” But there was also a definite change in Maggio’s relationship to the medium itself. “Drawing is a beautiful experience. To start to draw from life and to see it develop and to see it kind of jump out of the paper... it’s wonderful. I just lost, not interest, but I thought that I wanted to be a little more gritty, earthy, organic. And it got to be rote in terms of the process. So, I shifted.” Furthermore, “This is what I was teaching students. Later on, I wanted my work to speak more, to show more of who I was.”

Similarly, with respect to technique, the digging in of pencils, charcoals and erasers became the scraping away of paint layers with razor blades and other tools that facilitated the emergence of the image or imagery. And this engagement with new materials led to the discovery of different ways of achieving similar kinds of surface effects. The heavy paper that Maggio had begun to destroy gave way to many layers of paint on primed canvas that hid the surface of the support. “I built up a nice surface and scraped, and built up layers and layers and layers, and I felt real good about the painting growing out of the canvas, going through the prime, so the paint is in the fibers. It had that gritty, organic quality growing out of the surface not resting on it, which was important to me, and that’s where the ten or twelve layers of paint [are critical].” To accommodate his developing painting method–and align with the speed of his masterful draftsmanship–Maggio eventually developed custom paints with Dominic Fulciniti at Buffalo Paint and Wallpaper, a mixologist who was able to achieve thick, viscous black and white paints that are also fast drying.

This deep immersion in his craft brought a natural change in Maggio’s subject matter. “I switched to abstraction in 1995 only because I was thoroughly engrossed in my work. It was my job. I had the freedom to do that. And that was why I retired when I did.” But again there is a change in relationship to his traditional medium. That 1995 “switch” would take many years to fully root itself, and Maggio has returned to representation in his work several times since, as the abstract tally marks of the past indicating time’s passage occasionally gave way to an engagement with pressing topics of our here and now, as evidenced in the Black and Blue (c. 2021-2022), BludMud (c. 2023-2024), and Torn Fences/Snagged (c. 2015-2016) series. There is another more profound sense in which the abstract works for which Maggio is best known may themselves be decoys that draw you in to deeper meaning and personal reflection such that they function as talismanic portals to interior worlds, in a liminal space where abstraction and representation no longer function in the same way.

“When you are searching to discover who you really are and what you really want or have to say, you try all different kinds of things,” says Maggio. “I was experimenting a lot previously, but after that experience I felt like I was on the right track.” Maggio is speaking of a brief hospital experience in 1997 when his heart stopped beating and he began to levitate from his body, rising weightless and enveloped by a previously unknown light of extraordinary warmth, brilliance, and comfort. It is difficult for Maggio to put this overwhelming multisensory experience into words. Some of his later works approach the visual qualities of that experience in ways he considers successful–not all of them try–but it is less the appearance than the auratic presence of something “beyond” that Maggio seeks to reveal more broadly in his later works.

In this fulcrum period of simultaneous sea-change and continuity, Maggio’s guides and mentors also changed. The curator and critic Christian Viveros-Fauné, a close friend of William’s filmmaker son Joe, passed along a 1991 book called On Presence by the mid-20th century theologian and philosopher Ralph Harper (1916-1996), which Maggio read and reread. Of Mark Rothko (1903-1970), whose work Maggio knew from the Albright Art Gallery and trips to MoMA in New York City, but which had never previously held great interest, Maggio states, “I remember thinking, ‘I’d like to affect people the way Mark Rothko affects them, with my drawing in paint without color.’ This was when I first started to do black and white, around the time of my hospital experience.” And of the same general period, when discussing his long-standing fascination with “walls, wallscapes, and wall marks, which show the passage of time,” Maggio says, “I was [then] very much into Antoni Tapies” (1923-2012). At this moment, Maggio speaks in relation to his later Wallscapes Series (c. 2000).

Lest one think of these shifts as ruptures, however, Maggio recalls seeing the retrospective exhibition of Tapies’ work at the Albright Art Gallery in 1977, where he first became familiar with the artist, but it was a solo exhibition at the David Anderson Gallery years later that made a greater impression–long before Maggio’s own avowed turn in Tapies’ direction. “The organic quality of the work and how he incorporated unusual materials and combined them with paint really intrigued me. I felt it. I felt the message and got most of his work. A lot of it was religious, a lot of it was his feelings about war and death. He did a series on walls. He talked about walls that are figurative. It had a mental twist that was similar to my approach at that time from his own life. They were very moving, very stark.”

Another artist close to Maggio’s heart in recent years is Alberto Burri (1915-1995), whose posthumous retrospective exhibition, Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, Maggio saw at the Guggenheim in New York in 2015, although it is also quite possible he saw, absorbed, and held in his imagination Burri’s previous New York exhibition, thirty-seven years prior in 1978, in the very same venue. Maggio describes the recent exhibition as one “that just blew my mind. It was [Burri’s] reflection on the war. He used bloodstained stretchers from the war. His work was totally his own, so organic, and the marks and the tears, it had a rawness to it which I conjure up in my mind as so prevalent in actual combat, in conflict and war, this blood and flesh. Why do people do this to one another time and time and time again? And he captured it in my mind. This influenced me a great deal when I got back.”

Maggio sees and deeply appreciates the “material grit” in both Tapies’ and Burri’s work. Indeed, as Maggio states, “I see this in my own work, but it’s somehow polished.” Maggio’s further reflections that explain the difference of his own work speak directly to the complexity of continuity and rupture in his own professional development, and to a profound awareness of the rootedness of works in the lives of artists who make them, his own no less than others. “I think had I experienced the actual being in battle, as Burri had, and Tapies was a tortured soul as well, with his religion, I think their experience is so different from my experience growing up and getting to this point in my life... So they had hands on experience. Burri was a medic. What he did, what he saw, and what he retained, that was like really experiencing what the horrors of war must be like. I think of Guernica: as horrifying as it is, it doesn’t have the grittiness that Burri or Tapies has. It’s a surface kind of thing... I don’t want to say it’s ‘cartoony’ or ‘illustration,’ but it’s an image. I remember how impressed I was in college by Guernica, but things change as you get into yourself and experience the work of different artists, and meld into your work different things from different sources, and try to come up with your own vocabulary.”

Today, Maggio still plays the piano every night. “I find a lot of similarities between playing jazz and painting abstractly in terms of mindset,” he says. And he references Jackson Pollock (1912-1956): “He said all his paintings start out the same, but somewhere along the way they overpower him and take control, and then it comes to an end. That thought really stuck with me. Each of my paintings starts the same way, but each one is a separate journey. It’s key for me to know when the journey ends.” He adds that now, “within the last few years, it is the first time I really feel like an artist, that I have arrived, that my vocabulary is my own. That I have control, that I have mastered this process. I can see something in my mind, I know what I want the canvas to look like, and I know how I can get there by the way I manipulate the paint. This is what I do and what I know.

“There is a fine line between nothing and everything,” says Maggio, to which one might add there is a fine line between how the artist lives his life and how he makes his paintings, for the two are deeply entangled, continuously evolving in relation to each other, with all the experience of a more than sixty-year career of looking and making brought to bear. “Nothing is forgotten....” The fullness of the artist’s life experience remains a presence. And about his Burchfield Penney retrospective, Maggio reflects, “I don’t think of it as an ending but a beginning. There’s more that I want to do.”

And what does Maggio hope viewers will find in his work? “My work is not so much political as historical. The work is geared toward painting emotion and how I feel. I’ve always thought that my art should reflect the times. I’d like people to stop and look and think. If they can come into the work and be transported, maybe they can discover something about themselves, too. I’m not trying to take a political side or judge anything, I’m just trying to record my experience, what I feel. There is so much that bothers me, that just doesn’t seem right, and that feeling is what I bring to the studio. It’s what I feel day to day amidst all the news channels, social media. It’s a world of consideration. The things I’m thinking about and referring to in my work are universal. We’re all human. We all experience these emotions. My works reflect my life but are not culturally related. They are not unique to me or to Americans. I like to think it could be understood in other cultures and have a positive impact. The quality of spiritual presence–that there is something greater than man, some force, some presence. Something that is unique to all of us regardless of where or how we live our lives. I would like to have more people experience what I experience in their own way. I just want people to think internally about what’s good. We don’t have to be separate. I just want to get people’s attention about what life is–it goes by so damned quick.”

For more information on the work of William C. Maggio or to purchase a retrospective book please contact The Burchfield Penney Art Center: info@burchfieldpenney.org, 716-878-6011

art by william c. maggio | photos by mark dellas