connective threads

Everyone has a favorite t-shirt. The well-worn band tee from your very first stadium concert in high school. A faded one you bought at the playoff game your team won a few years back. The one you never returned to your college ex-boyfriend, now fraying along the seams. It’s comfortable and fits just right, but more than that it’s a touchstone for a moment in your life. You know exactly where you got it, what you were doing, who you were with.

What you probably don’t know is who made it. But there’s a pretty good chance that it was Jon Weiss.

“When people ask me what I do, my answer is pretty basic–I print t-shirts,” Jon Weiss says, a wry smile spreading across his face. “But to put it in the right context, I printed three million shirts a month. I bet I’ve printed a half a billion shirts in my life.”

His business, New Buffalo Shirt Factory, shaped sports and music merchandising for decades, continually introducing higher levels of quality, creativity, and production innovation, including a method of printing on dark fabrics that gave the world the now ubiquitous black concert t-shirt.

Throughout his career, Weiss has worked with top tiers of the music industry across all genres, including the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Garth Brooks, Madonna, Taylor Swift, and Jay-Z. He’s also enjoyed successful long-term business partnerships with the NFL and NBA, Harley Davidson, Nike, and Disney.

And while t-shirts made Weiss a success, the garment business has been woven into the fabric of his family for generations.

“I am the grandson of Eastern European Jewish immigrants who came to the States prior to World War I,” Weiss explains. “My grandfather was a sewer and embellisher who was very good at chenille and chain stitch, which was all done by hand at the time. He moved to Buffalo and he started a little decoration factory called Amco Monogram and Embroidery.

Weiss’ grandfather, Sam, was one of hundreds of thousands of Jewish Eastern European immigrants who came to America in the early 20th century seeking opportunity. Many had skills in garment work, skills that were in demand at the advent of ready-to-wear clothing manufacturing. The garment industry became a central element of Eastern European Jewish life in urban centers like Buffalo. Sam Weiss operated his factory on Washington Street in Buffalo for over three decades.

“All the people who worked for my grandfather were Eastern European,” Weiss recalls. “I wouldn’t call him purely entrepreneurial. I think it was more–hey, there’s nobody here that does this. I can do this and I can help out some fellow immigrants and provide income. That’s the way it all started.”

At a very young age, Weiss began accompanying his grandfather to the factory every weekend: “Every Saturday morning, my Polish grandfather would come pick me up in his Buick so he could show off his grandson. I would sweep threads from the factory floor and talk to all the old Polish women.”

As Weiss got older, he moved beyond sweeping and began to take on increasingly more complex jobs at Amco. The work was often difficult, and messy.

“We made work hats for factory workers, which was without a doubt the worst job I’ve ever done in my life–soaking straw and felt in formaldehyde,” Weiss says. “My grandfather was a bowler, so a good percentage of the business was bowling league shirts. When the graphics got too complicated to do by hand, we did a process called flocking, which is printing a specific ink on a shirt and then dropping ground felt over it. It was a filthy job.”

As graphics demands increased in complexity, the family business had to evolve as well. In 1973 Jon’s father Stanley incorporated Buffalo Shirt Factory to try their hand at screen-printing to modernize their services.

“They needed somebody to learn how to print,” Weiss recalls. “I was 13. So I learned how to screen-print on the fly. We were probably one of the first screen-printers in the city of Buffalo. My father was the salesman, I was the artist.”

Weiss didn’t realize it then, but he had taken the first step on his journey to make New Buffalo Shirt Factory a rock and roll merchandising empire. Though graphic t-shirts are now a mainstay of American culture and a multi-billion dollar business, that wasn’t always the case.

The first t-shirt was manufactured in the late 1800s. By the early 20th century, the U.S. Navy was issuing them as undershirts. The term “t-shirt” was first seen in print in the 1920 novel This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald. But it wasn’t until Marlon Brando and James Dean wore them on the silver screen in the early 1950s that t-shirts became more than a humble undergarment. Brando and Dean made white t-shirts the uniform of stylish rebellion, but it would take several more years for the t-shirt we know today to enter the fashion scene.

“It started in South Florida in the 1950s, when hotels started printing t-shirts for promotion,” Weiss explains. “By the late 60s, people realized it was a great way to market and advertise. We started doing promotional printing for Buffalo rock and roll bars who gave the shirts away for free. That led to work for radio stations and other customers, but it didn’t immediately pan out. It would be 20 years before the business really took off.”

During those two decades, Weiss explains, he at times had serious doubts about his career. Family kept him at Amco, and in his hometown of Buffalo, but the work was not his passion: “The last thing I ever wanted to do was to print t-shirts. And quite honestly for 20 years, from about 1968 to 1988, it was a job that I really didn’t like.”

But Weiss’ trajectory changed through a series of chance meetings, starting when he met Linda Nagle in the early 80s.

The self-described “creative black sheep” of her family, Nagle realized she was an artist at a young age, and by high school was already designing signs and promotional posters for local businesses. After graduation, she decided to skip college and instead went straight to work in advertising.

“I started doing ads for the ‘Pennysaver,’ a little weekly newspaper, and I cut the color for comics back when people still cut color,” she recalls.

Throughout her career, Linda worked as a calligrapher, designer, and art director in corporate advertising at a global agency. But her most consequential job may have been an accidental gig as a stand-in for a movie being filmed in Buffalo. It was this job that first got her noticed by Jon.

“The movie was Best Friends, starring Goldie Hawn and Burt Reynolds. I was visiting a friend at a hotel and the movie production team was staying there,” Linda explains. “Norman Jewison, the famous producer, was at the elevator, and he thanked me for coming to the audition. I had no idea what he was talking about. He said he’d like me to be a stand-in for Goldie Hawn because he could see the resemblance. And I said, ‘I’m not going to be anyone’s stand-in. I’m an artist and I am true to myself.

“Then they told me how much it paid,” she says, laughing. “I took the job.”

At the same time, Linda was working as a designer and was asked to accompany a client to deliver a logo she had designed to the t-shirt printer. The printer was, of course, Jon Weiss.

“I knew that she was Goldie Hawn’s stand-in, which intrigued me–she was on the front page of a local paper,” Jon admits. “I guess the rest is history.”

“It all started when he called me do some work for him, for 97 Rock, a local radio station,” Linda says. “It was probably the worst piece I ever did. And he still fell in love with me!”

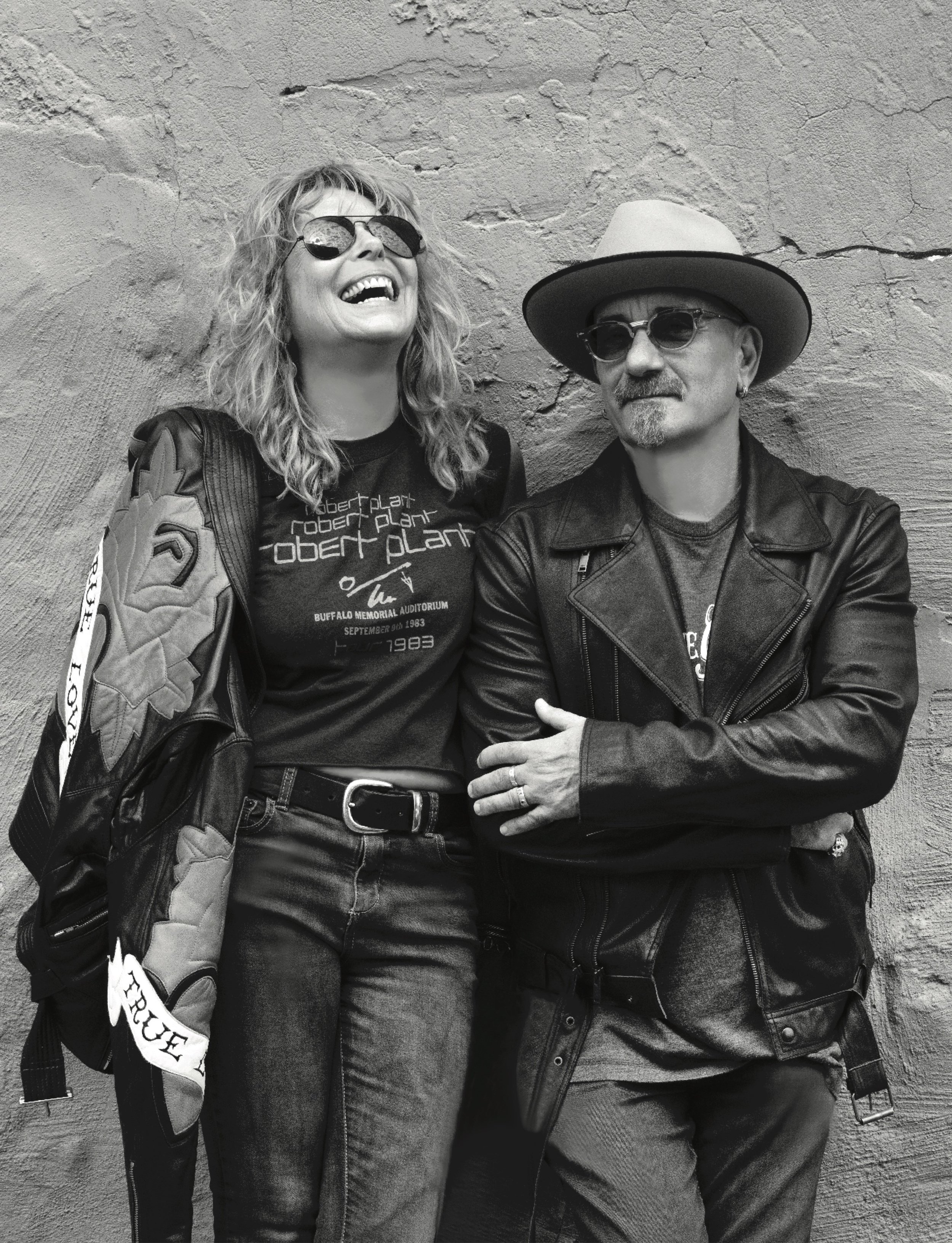

The two began working together on designs first, then began dating in 1982. They married in 1986. Linda would go on to serve as an executive for New Buffalo Shirt Factory for 30 years.

Early in their marriage, Jon remembers coming home some nights and telling Linda that he was done with the family business, that he couldn’t do it anymore. Working alongside his father was difficult, the business was struggling, and Jon was finding it harder and harder to stay engaged. By then, Linda was doing work for New Buffalo Shirt Factory, while working at local advertising agencies. What they didn’t know was that a moment of odd serendipity was about to change everything.

“My hobby was building choppers. I was working for $1.85 an hour, so I couldn’t really support my motorcycle habit. But what I could do was trade t-shirts for motorcycle parts,” Jon explains. “But sometime around 1982 or 1983, Harley Davidson became a trademark company and you could no longer print Harley Davidson on a shirt. Only three people were allowed to print Harley Davidson t-shirts and one of them did printing like I’d never seen before. The Buffalo Harley store owner told me that this guy was an artist originally from Buffalo, Dave Gardner.”

In 1988, Jon answered a call in his office from an artist looking for a screen-printer. A few minutes into the conversation, Jon learned that the 32-year-old artist had just moved back to Buffalo after living and working in Fort Worth, Texas.

“I knew the Harley licenses were with an artist in Fort Worth, so now he’s starting to pique my interest,” Jon explains. “I asked him his name.”

The artist on the other side of the phone was Dave Gardner.

“And I said, ‘I’m such a huge fan of yours,’” Jon remembers, still incredulous about the unlikely connection all these years later. “I told him, ‘I’m wearing a shirt of yours right now!’ Pretty rare to call a guy who happens to be wearing one of your shirts, but this is how fate works, right?”

The two men set a meeting. Jon knew the scale of his business was likely not a good match for Gardner’s talent, but they hit it off, bonding over their love of Buffalo sports: “We were both huge Bills and Sabres fans so I said, ‘Hey, I have

an idea.’”

He proposed that they collaborate on a shirt for the NFL in Gardner’s signature Harley Davidson style. Jon had a local friend who he thought might be able to get them a meeting with the NFL. Gardner quickly agreed to the project.

“Dave was a brilliant painter and art separator, and a dark room genius,” Jon marvels. “He took a picture, went into his personal darkroom, developed it, airbrushed it, and then pulled the color apart. This was all before Photoshop. The entire process probably took a week non-stop.”

Once Gardner’s artwork was complete, the two men met at Jon’s factory to screen-print the design.

“We burned all the screens, did the stencils, set it up. It was probably two in the morning and we’d worked all night,” Jon says. “I ran three shirts and I couldn’t believe my eyes. The work was just incredible.”

Jon went home to Linda in the early morning hours, the sun just starting to light up the sky over Buffalo.

“I throw the shirt on my bed and tell my wife, ‘We are going to be millionaires!’ Jon says, laughing.

Gardner and Weiss did land a meeting with the NFL in New York City. But like the stories of so many entrepreneurs with an idea, their vision was not immediately apparent to the decision makers they’d need to bring their design to the masses.

“They threw us out because it was a big boys club and we were not big boys,” Jon says, a hint of anger still palpable in his voice. “But as we were walking out, the director of licensing stopped us and said he wanted to show our work to his art director. That was my big aha moment–I realized we had something very special.”

There was no deal that day, but Jon was undeterred. Convinced he and Gardner were onto something big, Jon felt a new energy in his work and he wasn’t ready to let a single “no” put an end to it.

“We went out and licensed with about 30 universities and created a brand called ‘Intense Mascots,” Jon says, explaining the risky move that changed the trajectory of his career, and his life. “When we did our first show, it just blew up.”

Gardner brought an edgy design vision and the process he’d invented for printing high color-count screen-prints on dark fabrics. Weiss brought his business knowledge, his never-quit drive, and the printing expertise he’d honed since he was just 13 years old. It was an equation that worked–the product was unlike anything in the industry at the time.

“They called us ‘The Kings of Black,’ because all we were doing were black shirts,” Jon explains. “Dave invented the process and I perfected and marketed it. It really disrupted the industry … And that’s how we worked for ten years. It was an incredible run.”

At this turn in the narrative, Jon’s voice and demeanor change. What was at first the story of a hard-scrabble family business and a dutiful son becomes something else. He leans forward, his voice charged with an energy that wasn’t there before.

“I’ll tell you what–back then, we worked our asses off,” he says. “We just had so much work to rock and roll. And it was fun. People tell you to be successful you need to find something that you’re passionate about. But I like the quote from Scott Adams, the author of Dilbert, who said, ‘That’s not quite it–you need to find success and then you’ll find passion.’ And that’s kind of how it was for me.”

As Jon became the center of gravity for his family’s business, taking over management, the company steadily became an industry powerhouse. He charted a fresh path forward, so that by the early 1990s, New Buffalo Shirt Factory wasn’t the traditional family business it had once been.

Still, even as the company changed, Jon found himself relating to his grandfather in new ways. Like the elder Weiss, who had founded a small embroidery company not just for a living but also for a community of immigrants seeking better futures, Jon found more than a revenue stream in his business. His voice softens as he describes paying his employees more than one million dollars in bonuses over the course of two banner years, money that enabled some employees to put down payments on homes, or purchase much-needed new cars.

“In many ways, Jon was the head of the Buffalo and I was the heart,” Linda says. “Our corporate culture was like a family. We were young when we hired these people and they were with us for 20 years. We were at their weddings, we were at their babies’ baptisms. We grew up together.”

While Jon and Linda built a new kind of family business at New Buffalo Shirt Factory, they also built their own family at home. Their son Max was born in 1990 and their daughter Dylan followed a couple years later.

Max, now 33, is a musician, graphic novelist, and life coach for young adults. Dylan, now 30, is a rising star in Chicago’s real estate scene.

As their children became adults, with their own dreams to follow, Jon and Linda made the decision to sell New Buffalo Shirt Factory to Gildan in 2013. Two years later, they were both officially retired.

But retirement didn’t suit Jon, who had devoted his entire life to learning, building, and running his business. He felt adrift, so he did the only thing he knew how to do: He went back to work, partnering with a long-time friend and New Buffalo employee to revive the brand.

The rights to the New Buffalo Shirt Factory name still belonged to Jon, so he and his partner launched a new business under the brand, dropping only the word “Factory.” Jon was back in business.

“You know, anything could happen,” Jon says, a familiar energy in his voice as he talks about his new venture. “We recently moved into a new building that is twice the size and we’ve increased our capacity two-fold. I’m happy to say it’s doing really well.”

In a lot of ways, Jon and Linda Weiss are emblematic of the baby boomer generation, who are defying expectations of aging, working longer, reinventing themselves, and not letting time and age define their paths.

“Honestly, we never had the chance to grow old because our business was so demanding and so young,” Jon explains. Still, he acknowledges that he is seeing significant changes in his industry. “You know, we brought a unique style of printing to the rock and roll merchandisers, and all of my clients were older than me. They’re all in their 70s–and some of them are dead. They’ll all eventually age out, but rock and roll will never die.”

The iconic t-shirts, though, are not aging out. Vintage t-shirts are in high demand, with rare finds often commanding hundreds of dollars at online vendors like Etsy, eBay, and Depop.

Jon says that New Buffalo Shirt Factory designs are difficult to find at vintage retailers, something he attributes to the fact that fans simply do not give them away.

“I was sitting in a bar in Costa Rica, talking to a guy, and I told him that my first gig with the Rolling Stones was the Bridges to Babylon Tour in 1997. And he said, ‘Oh my god, that hammered gold tongue shirt–I tried to buy it in Japan and they wanted 450 dollars for it,’” Jon says incredulously. “My son has become an unbelievable collector of my old work. That means more to me than anything. Every time he shows me a shirt of mine that he bought, it touches my heart.”

Jon gestures toward his collection of signed electric guitars, hung on the wall behind him, a colorful timeline of a life spent on the edges of rock and roll.

“When my son passes these down to his kids, that will tie them to the story of the family business and what we did, but I don’t necessarily want to be remembered for the business,” Jon says. “We’ve worked with the best of the best as a fringe player. I’m super proud of the people that we’ve had the opportunity to work with. But I think the greatest thing is our family.”

In many ways, the threads that bind family will be the enduring legacy of New Buffalo Shirt Factory. A legacy that began with a community of immigrant families welcomed to America by Sam Weiss and his company, Amco Monogram and Embroidery. A legacy grown by New Buffalo Shirt Factory employees who printed millions of rock and roll t-shirts and became family along the way. And a legacy that continues each time a customer pulls on their New Buffalo-made t-shirt and remembers the moment, the feeling, and the people that soft, faded shirt evokes.

And, of course, there is the dutiful grandson who joined the family business, convinced at so many moments along the journey that he had made the wrong decision, but somehow getting it right in the end.

“There was a local businessman who was one of my first clients when I did a shirt for his bar,” Jon recalls. “He pulled me aside when I was 16 and said, ‘Junior, I’m gonna give you the best advice you’ll ever get in your life: You never make wrong decisions. The ones that appear wrong aren’t–you just have to work really hard to make them right.’”

More than 50 years later, Jon Weiss is still working, and that’s exactly how he likes it.

photos by m. dellas